Imagine going on a sabbatical from your job, a job you’ve had for 10 years, a career you’ve been aspiring to for over 20 years. Safe to say you’re going to feel a little unmoored, a little brave stepping out into something new, a little bit excited about a change of pace.

Now imagine telling people about it and their reaction is not to sympathise or celebrate or commiserate. Instead, their response is to slowly look you up and down and say:

"It doesn’t look like you’ve put on much weight, yet."

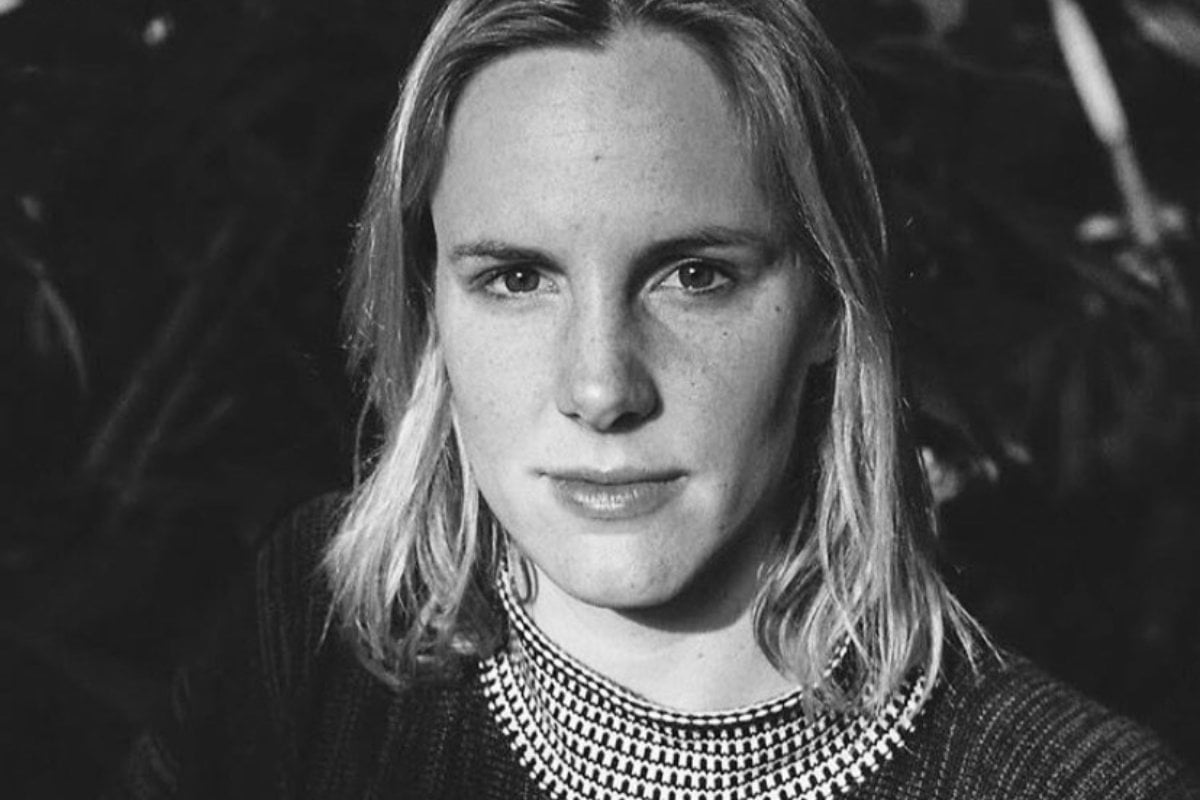

Watch: Cate and Bronte Campbell talk about their relationship. Post continues atfer video.

After the Tokyo Olympics, I took an extended break from professional swimming during which time I got this comment a lot. Not a little bit, a lot.

It’s been 18 months and I’m still not sure, how are you supposed to respond to this?

So far my go-to response is: I smile, fake laugh and change the topic.

It’s easier to pretend that you haven’t noticed anything weird in the question. There are always some awkward encounters when you’re a professional athlete. Usually, it’s strangers asking me about my sister, asking me if I’ll ever be better than her (my older sister and I compete in the same events). I know that sometimes the familiarity we feel for our sports people, makes us feel we own some of their narrative and can ask very personal questions. Perhaps it was partially this familiarity that fed these weight questions, I don’t think many of us would think twice about telling a friend they looked fit after they’d finished training for a triathlon.

Top Comments