Warning: this post discusses domestic and family violence.

Over the past four months, Australia has lost 31 women to male violence.

Most were allegedly murdered by men they knew. Many were murdered by men they trusted. Men they loved.

These are not random homicides. They are the result of gender-based violence. These women are being murdered because they are women. According to the Australian Institute of Criminology, the number of women killed in intimate partner homicides increased from 26 in the year to July 1, 2022 to 34 in the year to July 1, 2023. That's a 28 per cent increase over 12 months.

Watch the PM talk at the weekend's No More Rally. Article continues after the video.

For those in the space, for women, it feels like we’ve been making noise for years. We’ve been screaming, begging for action, for change. Begging for our lives to matter, to be worth something. To be worth at least as much as victims of other violent crimes, such as religious terrorism or coward punches.

We’re begging for men to understand that domestic violence is not just our problem. It's their problem too.

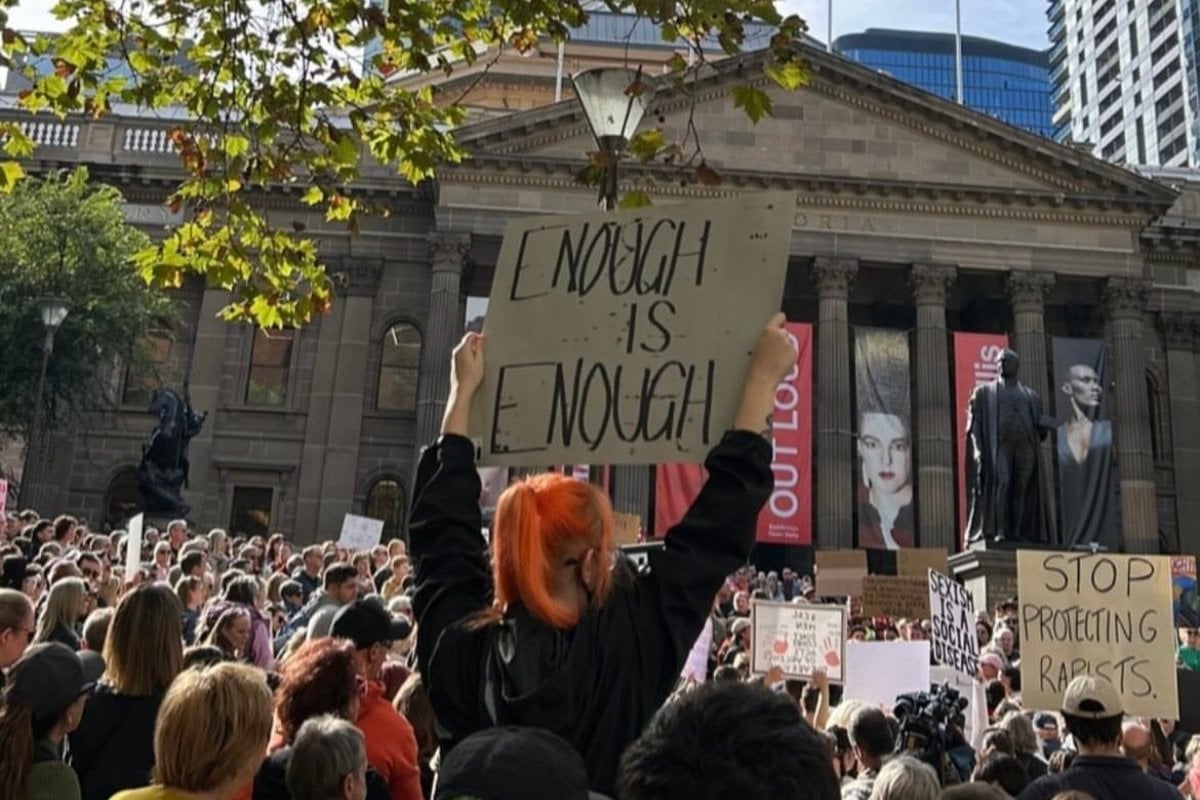

This year, we’re making more noise than ever. We’re speaking loudly. And often. The weekend’s incredible rallies are a testament to this.

Top Comments