Shane Cuthbert was once dubbed Australia’s “most evil husband”.

A current affairs program that ran a story alleging serious criminal allegations including rape, deprivation of liberty, and grievous bodily harm gave him the title. When the charges against Cuthbert were dropped, media outlets quickly removed their articles, but the damage was done. And while he wasn’t found guilty of the offences reported, Cuthbert wasn’t innocent either.

"I have perpetrated violence and have been convicted of domestic violence-related offences, such as wilful damage and breaching domestic violence orders," he admits.

Cuthbert has been imprisoned four times, spending 12 months in jail for multiple offences that he says he didn't take seriously at the time – even turning up to court wearing a clown suit on one occasion.

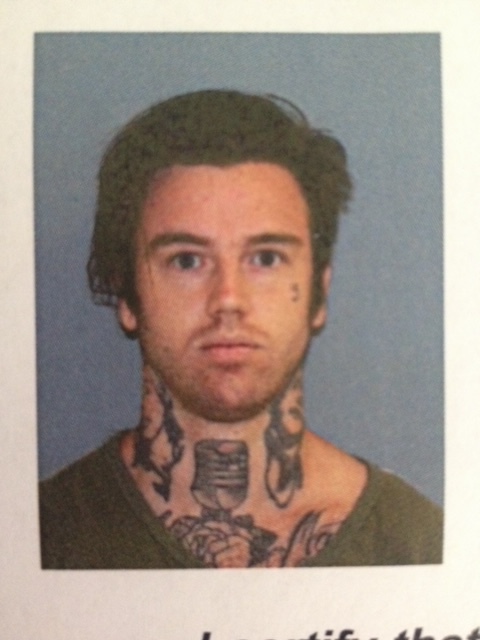

Shane Cuthbert. Image: Supplied.

Shane Cuthbert. Image: Supplied.

Top Comments