There is a small fact about the modern world I learned in my early 20s out of necessity: if you take all of your money out of the bank, nobody can take it from you.

At least, not that pay week.

Oh, everyone wanted it. My debt collector, Lee, was after me for my unpaid credit card. The mobile phone company demanded payment, so did the Queensland government for my speeding fines because I was “going too fast” on a “public road”.

So, out of an explicit desire to eat and make rent, I would stroll down to the same ATM each week and withdraw the entire contents of my bank account in cash. This was the kind of habit that forms in the fraction of a second. It didn’t start as an explicit plan. Nor did it come as a suggestion from anyone else in my life. It had never occurred to anyone to do the same because they had the financial means, even in tight weeks, to make ends meet.

They even had a safety net.

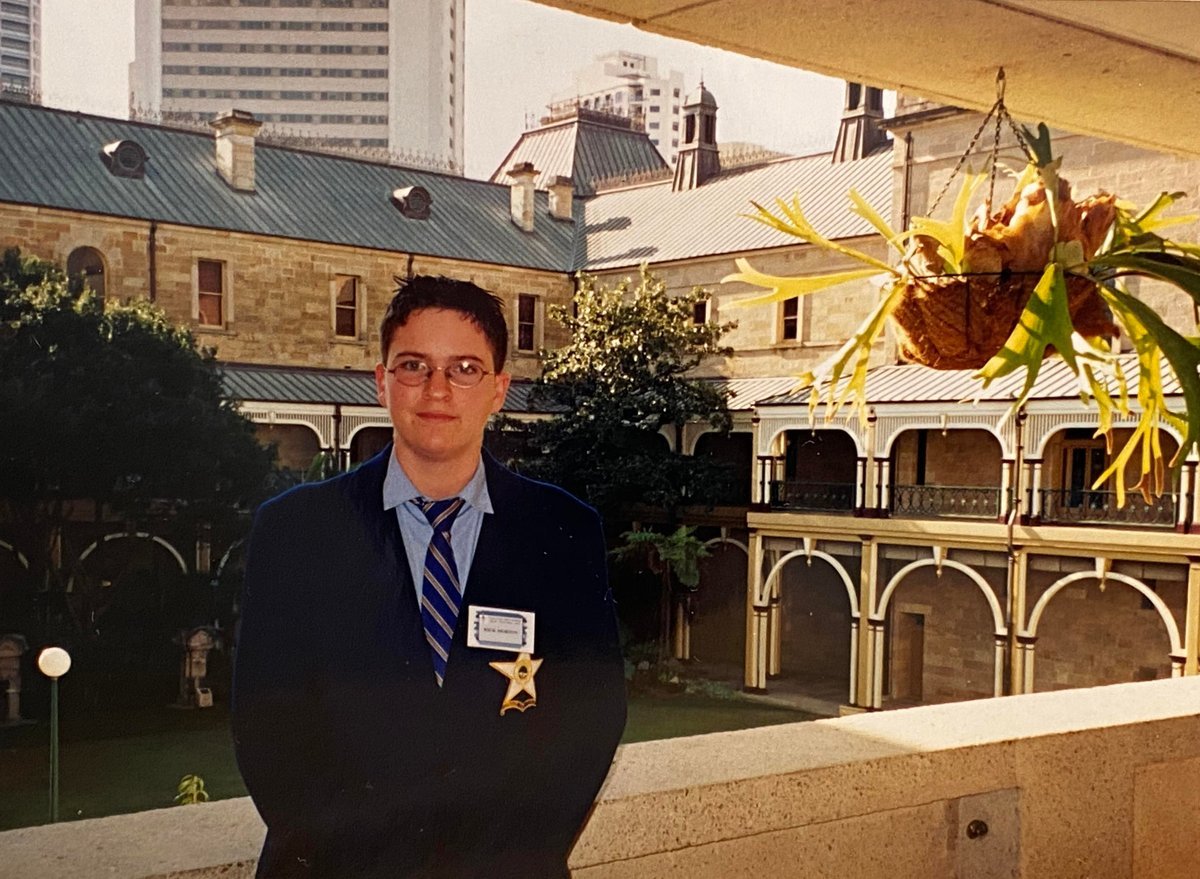

Rick as a young boy at a cattle station in far west Queensland. Image: Supplied.

Rick as a young boy at a cattle station in far west Queensland. Image: Supplied.

Top Comments