This article discusses psychosis and may be distressing for some readers.

It was a morning in February, 2014, as Osher Günsberg sat in a Los Angeles cafe with a coffee and a copy of the New York Times, that a terrifying thought descended on him.

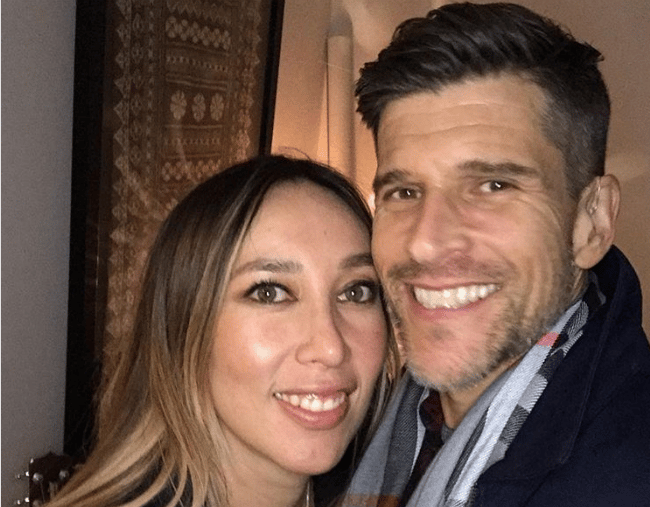

The then-39-year-old, who had hosted the first season of Australia’s The Bachelor the previous year, was unemployed and living in LA as he waited to hear whether the show would be renewed.

He was in an intense relationship (his first serious relationship since becoming sober), his father was very ill, and he had been off his anti-anxiety medication for about nine months.

At that time, on that day, and without warning, he started to lose touch with reality.

The article Günsberg was reading on that Friday morning in February happened to be about climate change. In an interview with Mia Freedman on the No Filter podcast, he recalled how “something popped into my brain”, and to this day, it hasn’t entirely gone away.

In one moment, he became “100 per cent convinced that the full, catastrophic ramifications of the worst possible case scenario projections of full climate change were happening, and they were happening today”.

It was as though all of a sudden he knew “the seas are going to rise 15 metres, the earth is going to warm up 10 degrees and all food storage and food transportation and everything, our whole way of looking after ourselves and looking after our lives and the lifestyles that we live, will vanish”. Günsberg was certain he was the only person who had full knowledge of, and cared about, this imminent danger.