Our collective appetite for true crime content is insatiable.

We obsess over certain cases, intent on uncovering who the perpetrator is, the evil committed, and every detail in between. We also wonder deeply about the victim. What were they like as a person? Who did they love? What were their final moments like?

It often comes from a well-intentioned place, where society is hoping for answers and justice. But there are times where it crosses a line, and snowballs into something ickier - a true crime addiction if you will.

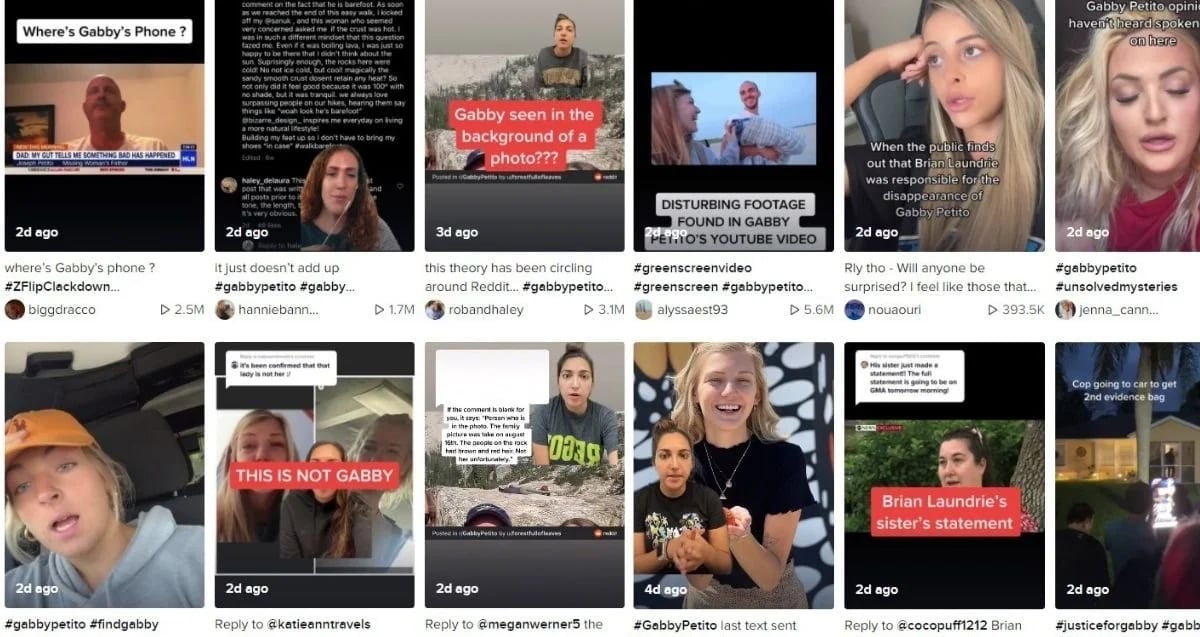

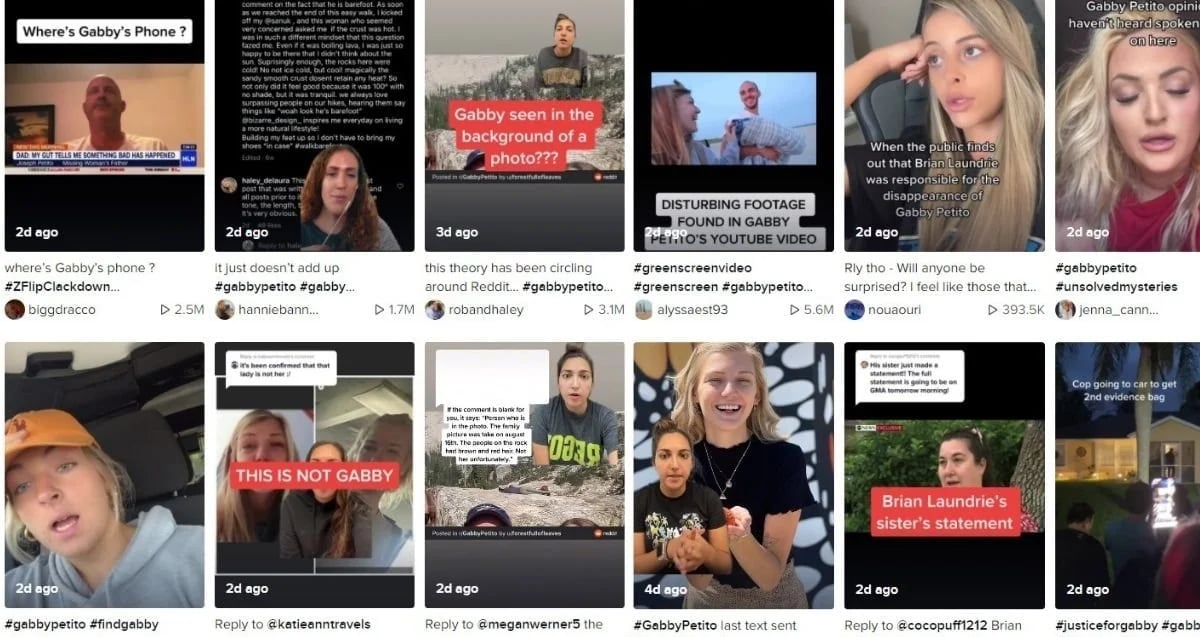

There are two recent cases that spring to mind. One is the disappearance and murder of Gabby Petito.

Her name will be familiar to millions around the globe, the young American woman's image was shared far and wide on the Internet.

Watch: The moment the FBI confirmed they had found Gaby Petito. Post continues below.

In late 2021 there was a major police hunt for Petito's boyfriend, following her disappearance. Prior, the pair had set out on a cross-country road trip in a van across America, documenting their travels in vlog-style videos posted online. But as her account grew silent suddenly and her family couldn't get hold of her, it resulted in serious concerns for her welfare.

Top Comments