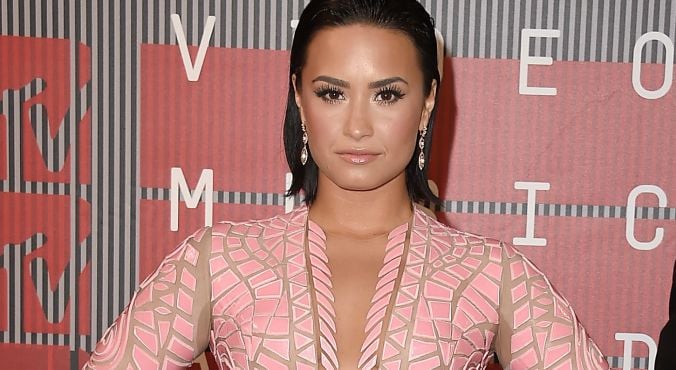

Image: Clare Stephens (supplied).

In 2014 I worked as a mental health worker with girls suffering from eating disorders.

I was living in Boston, where they provide the option of residential treatment for eating disorders, something they are just starting to introduce in Australia.

To an outsider, the centre looked like your typical suburban Boston home. It had a few bedrooms, with two or three beds each, a dining room, a kitchen, a living room, a few smaller rooms for individual counselling sessions, and a few bigger ones for group therapy.

The fact that this house was being used to treat one of the most deadly psychiatric conditions was only discernable when you looked closely at the details.

The locks on the bathroom doors and the pantry. The small nurses’ station set up near the living room for taking blood tests and administering medication. The affirmations that sat colourfully at the dining table. The 24/7 supervision, and the strict, individualised dietary plans displayed in the kitchen.

These girls were very sick, and I thought my education in psychology meant I understood what they were experiencing. (As a side note, males develop eating disorders too. But the higher incidence among females means that many treatment programs are targeted specifically at girls and women).

Watch: Could anorexia be genetic? Watch MamamiaTV’s discussion. (Post continues after video.)