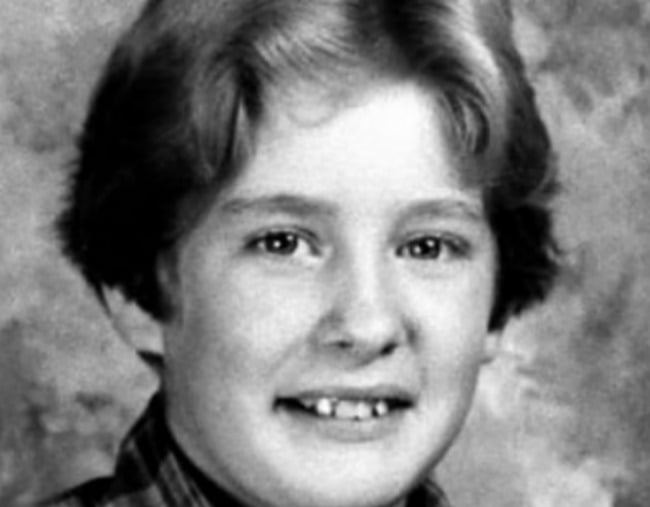

On the morning of September 29, 1982, a 12-year-old Chicago girl called Mary Kellerman woke up with a headache and a sore throat. She took some Tylenol painkillers and then collapsed in the bathroom.

“So I opened the bathroom door, and my little girl was on the floor unconscious,” her father Dennis Kellerman told the Chicago Tribune. “She was still in her pyjamas.”

Mary was rushed to hospital, but by 10am that morning, she was declared dead.

That same day, a young, healthy postal worker called Adam Janus took the day off work because he was coming down with a cold. At midday, he picked up his kids from preschool, and on the way home, stopped at the local store to pick up some Tylenol. When he got home, he took a couple of capsules, then collapsed. He could not be revived.

Late that afternoon, Adam’s family were at his house, planning his funeral, when his younger brother Stanley asked for some Tylenol to ease his back pain. His wife Theresa gave him two capsules, then took two herself. He collapsed, then she collapsed.

After a death and two collapses in the same house, Chuck Kramer from the Arlington Heights Fire Department called “the only public health person I know”, a nurse called Helen Jensen. Jensen walked into Adam Janus’ house and took a quick look around. She saw the bottle of Tylenol with six capsules missing and decided that was the cause of death.

“And of course nobody would believe me,” Jensen later told Chicago Magazine. “And I stamped my feet. They said, ‘Oh, no – it couldn’t be. It couldn’t be.’”

An investigator with Cook County’s medical examiner’s officer, Nick Pishos, got a hold of Janus’ Tylenol bottle, as well as the Tylenol bottle from the Kellerman house. His boss, deputy medical examiner Edmund Donoghue, told him over the phone to open both bottles and sniff them. Pishos reported a strong smell of almonds. Both he and his boss knew what that meant: cyanide.