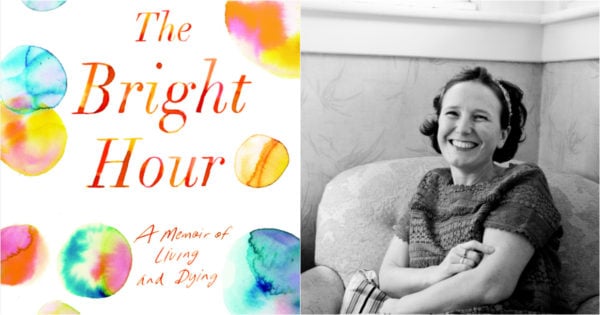

Nina Riggs spent the last six months of her life writing The Bright Hour—a hilarious, heartbreaking book about how to go on living when you know you’re dying. It’s about parenting, love, sex, grocery shopping, finances, chemo and radiation—the mundane and the absurd, the spectacular and the terrifying. Nina died in February this year, leaving behind her husband John and their two small boys.

The call comes when John is away at a conference in New Orleans. Let’s not linger on the thin light sifting into our bedroom as I fold laundry, the last leaves shivering on the willow oak outside—preparing to let go but not yet letting go. The heat chattering in the vent. The dog working a spot on her leg. The new year hanging in the air like a question mark. The phone buzzing on the bed.

It’s almost noon. Out at the school, the kids must be lining up for recess, their fingers tunneling into their gloves like explorers.

Cancer in the breast, the doctor from the biopsy says. One small spot. One small spot. I repeat it to John, who steps out of a breakout session when he sees my text. I repeat it to my mom, who says, “You’ve got to be kidding me. Not you, already.”