An honest and powerful essay on being a Muslim mother in Australia right now, beautifully written by the sociologist Susan Carland.

It was after reading yet another Facebook update by a friend saying she had been spat on by a stranger in public that something inside me shrivelled down on itself.

I closed that tab and opened a new one for my email. In a stream of hot tears and hot words, I emailed my daughter’s teacher. I used words like ‘terror’, ‘safety’, ‘attacks’ and ‘alarming’. Sharp words that cut through space and cut through my heart. I cried as I typed an email asking my daughter’s teacher to keep her safe when I wasn’t there.

When I was overdue with my first child—the daughter at the centre of this piece—I went to the hospital for a check-up. After some tests, the midwife informed me that my baby was lying in a posterior position, meaning her spine was pressing into my spine and causing the terrible agony I felt in my back. She also said that much of my baby’s amniotic fluid had drained out. The liquid life that had surrounded her had slowly trickled away and I had not even noticed. How could I not notice? My baby was already slipping through my fingers, unobserved.

The midwife insisted my baby was very ready to be born. She needed to be born, and quickly, for both our sakes. And yet my body didn’t want to push her out and she appeared in no hurry to leave. We both seemed to want to stay attached, even if it hurt us.

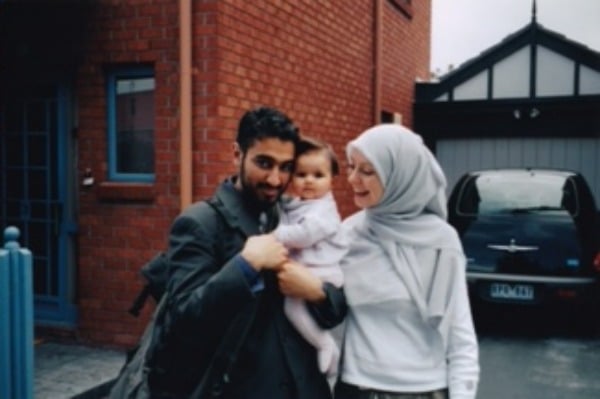

But in honour of survival, I pushed my daughter through a ring of fire and into the world when I was just 23 years old—a young mother by modern standards. I cried with delight when the nurse placed her on my still-gasping chest and told me she was a girl; I had so desperately wanted a girl.