In 1959, Richard and Mildred Loving were given two options: Spend time in jail, or leave the only home they'd ever known in Virginia for 25 years.

Their crime, in the eyes of Virginia law, was love.

Richard and Mildred had met seven years earlier, when Richard was 17 and Mildred was 11. Richard, a labourer and construction worker, was a family friend, close with her older brothers.

Their home of Central Point was an anomaly in its part of the world, where Jim Crow laws meant segregation throughout the Southern states of America.

While races were divided everywhere else, they had long been intertwined in Central Point.

People of different races worked together on farms and drag-raced together, a hobby Richard was particularly fond of.

So it wasn't so strange that Richard and Mildred, nicknamed 'Bean' at the time, met when he visited her family home.

Years later, friendship evolved into courtship, which evolved into love.

An arrest and life in exile.

In 1958, aged 18, Mildred fell pregnant with their son Donald and the couple travelled to Washington D.C. where they were legally married.

The Lovings returned home as husband and wife, but six weeks later on July 11, the couple were jolted out of bed at 2am as the local sheriff entered their home and arrested them.

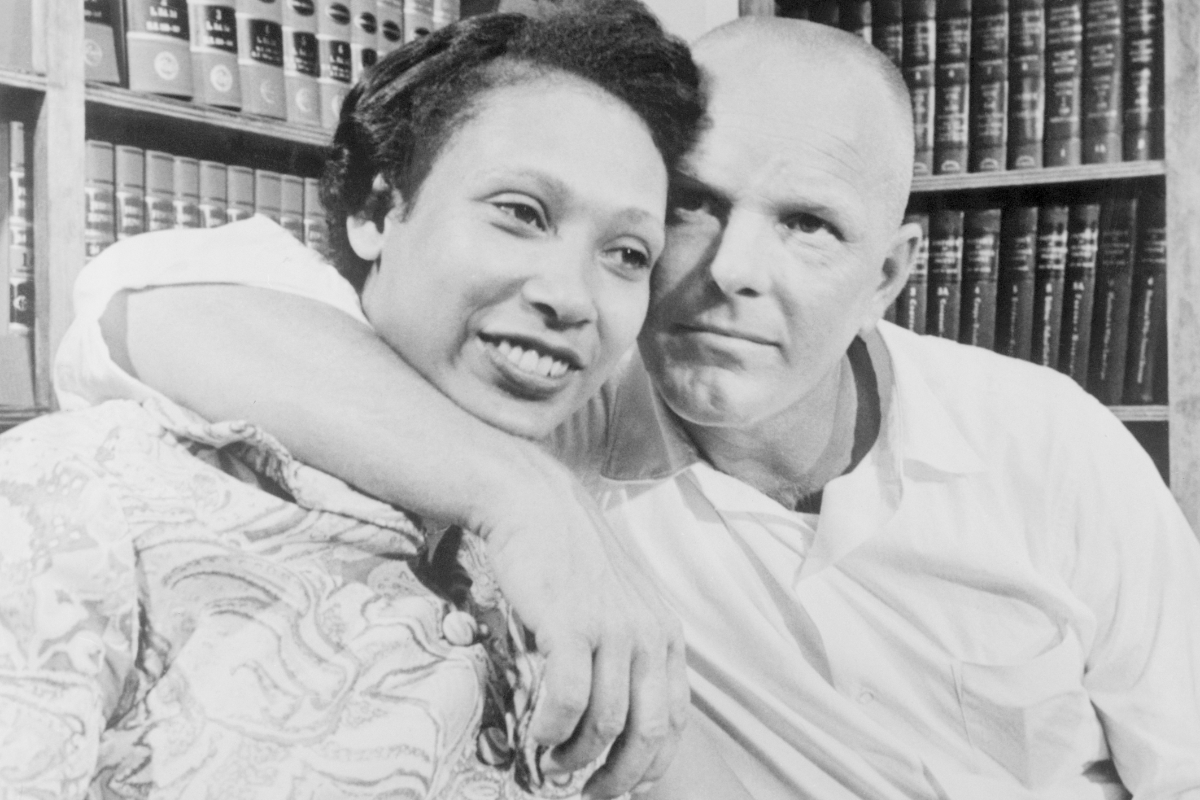

Mildred and Richard Loving. Image: Getty.

Mildred and Richard Loving. Image: Getty.

Top Comments