When Henrietta Lacks died, she left behind five young children, and one of the most important medical legacies in history.

She was just 31 years old when she passed at John Hopkins Hospital - the only hospital in her hometown of Baltimore, Maryland that treated black patients - of cervical cancer.

It was 1951, and Lacks died not knowing that only months earlier doctors had taken two samples of her cells without consent or compensation during treatments. One was of healthy tissue, and the other was cancerous.

Lacks died on August 8th of that year. While her body was in the hospital's autopsy facility, more cells were taken.

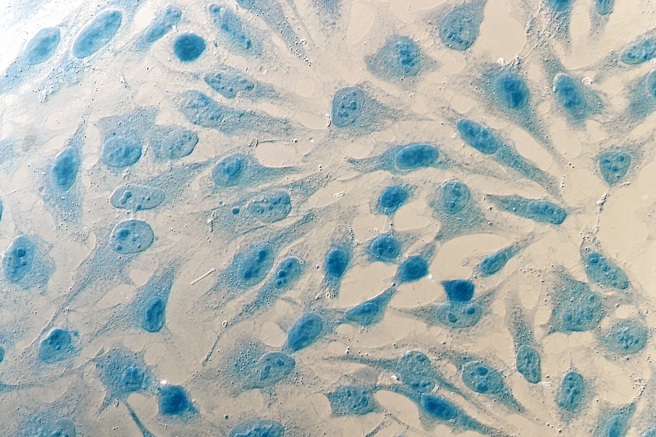

Because Lacks' cells were unique. They were "immortal".

John Hopkins' physician and cancer researcher George Otto Gey had observed that her cells reproduced at a very high rate and could divide multiple times without dying, long enough to allow more in-depth examination. Until then, cells in lab studies had only survived for a few days at most.

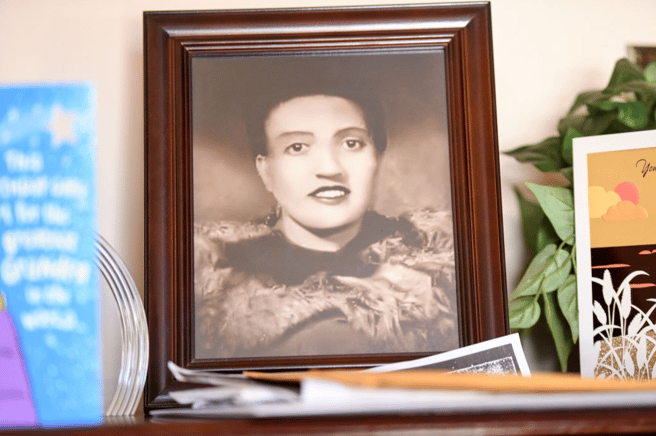

The life of Henrietta Lacks.

Henrietta Lacks. Image: John Hopkins University.

Henrietta Lacks. Image: John Hopkins University.

Top Comments