Trigger warning: This article discusses suicide and may be distressing for some readers.

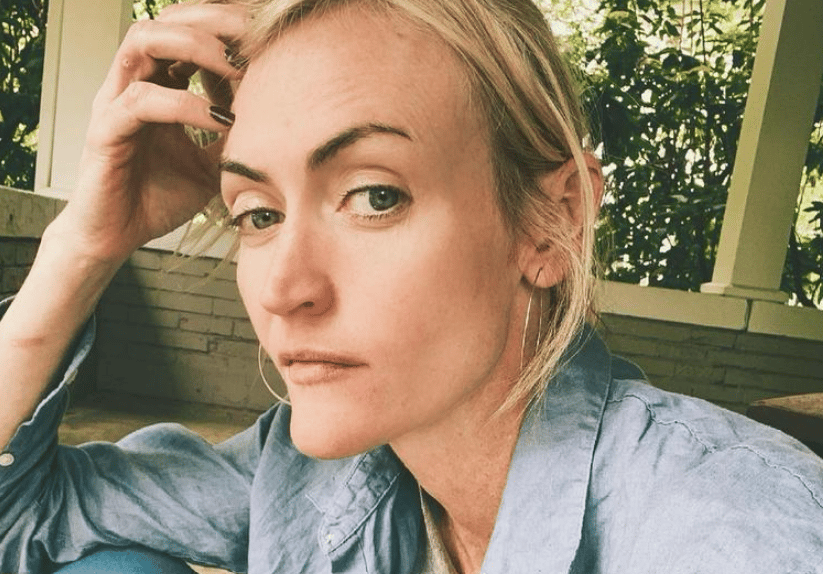

When blogger and author Heather Armstrong died last week, at just 47, she was widely eulogised as the 'Queen of the Mummy Bloggers'.

Armstrong started her blog, Dooce, in 2001, and over the next decade showed how a woman in the internet age could, as the New York Times described it, "make her life into a living".

But as one of the 'original influencers', she couldn't have possibly anticipated what that kind of life entailed. That she had signed up to a life marked by strangers' opinions, and that those opinions would continue even after she died by suicide.

In the days after Armstrong's partner confirmed her death to the Associated Press, thousands of tributes were posted online. A number of Armstrong's contemporaries referenced the hate she'd received as a public figure, and how it had affected her. Armstrong herself referenced how her mental health had been impacted by the commentary about her in an interview with Vice in 2019, describing it as "untenable". But in one dark corner of the internet - where the hatred for Armstrong had been unfolding for years - a group of people became immediately defensive.

Between profoundly cruel remarks about Armstrong's suicide and what it means for her family, the consensus was: She's not exempt from criticism and commentary. We're not going to absolve someone of their sins just because they've died. And if you live a public life, this is the price you pay.

Top Comments