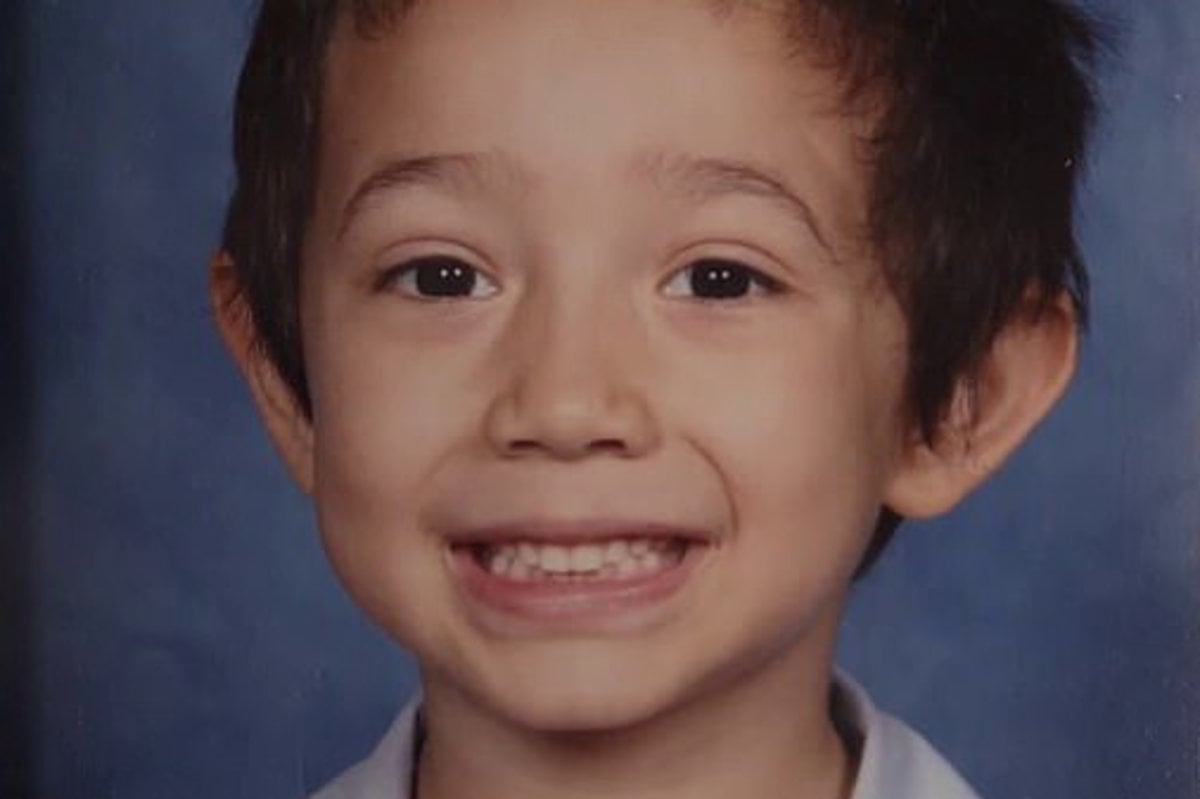

Michael* was a loving, devoted father.

He and his young son, born in 2012, were inseparable.

Michael had lived with schizophrenia since being diagnosed in 2003. He was medicated and lived a normal life, but when his son turned five, Michael's partner Anne* began to notice a change in his behaviour.

Four Corners' investigation: Violent crime and the mentally ill. Post continues below video.

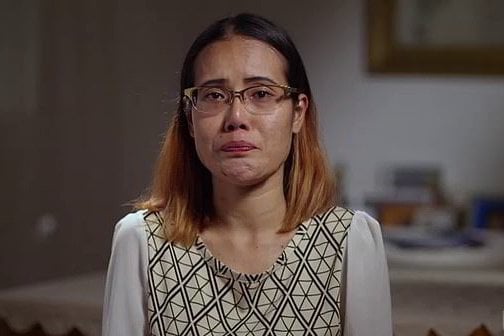

"He got a little bit confused and was talking about the devil, God, something like that. And he kept repeating the same conversation," Anne told an ABC Four Corners investigation.

Michael presented himself to a Sydney hospital to have his medication reviewed, but doctors presumed his psychosis was brought on because he was no longer taking his medication.

But he was, and the dose was no longer working.

Doctors prescribed Michael a lower dose of an antipsychotic medication than he had previously been taking, meaning his condition further deteriorated once he was discharged, 28 days later.