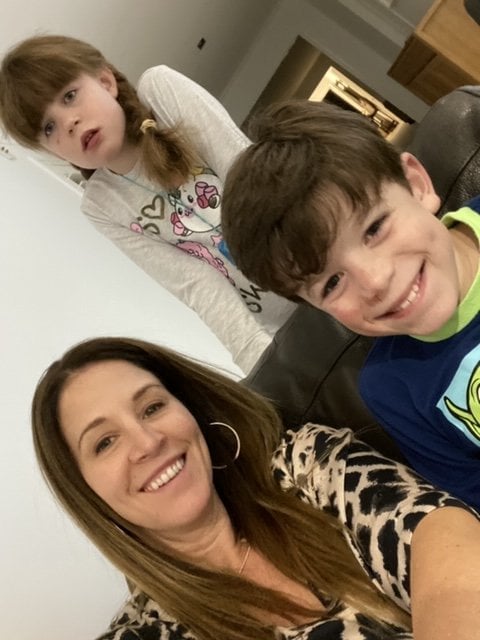

Megan Donnell used to jump straight to words like 'sassy', 'fashionable' and 'engaging' to describe her eldest child Isla to strangers.

She'd always had a gift for charming people with her talkative, vivacious personality, and would wow her parents with innovative dress up combinations. She had an infectious eye for style.

She's 11 now. But Megan can't describe her like that anymore, because that version of Isla is no longer here.

Watch: No child should suffer from childhood dementia. Post continues after video.

"The last 18 months to two years have been really tough on her. She has declined and regressed quite a lot. She can no longer talk, she is incontinent, she is minimally engaged. She has concentration difficulties, confusion, and disorientation. We had a bad year last year where I thought we'd never see her laugh or smile again," she told Mamamia.

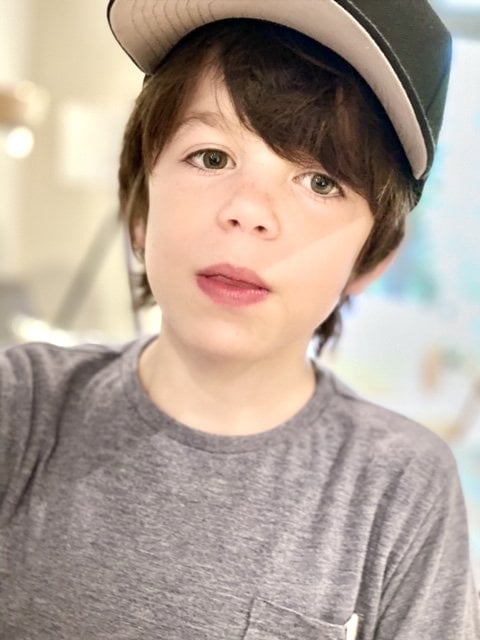

Isla has Sanfilippo syndrome, a rare genetic condition and a type of childhood dementia. Her little brother Jude has it as well, but while they both have an intellectual disability, nine-year-old Jude is yet to show any major signs of regression like his sister.

Top Comments