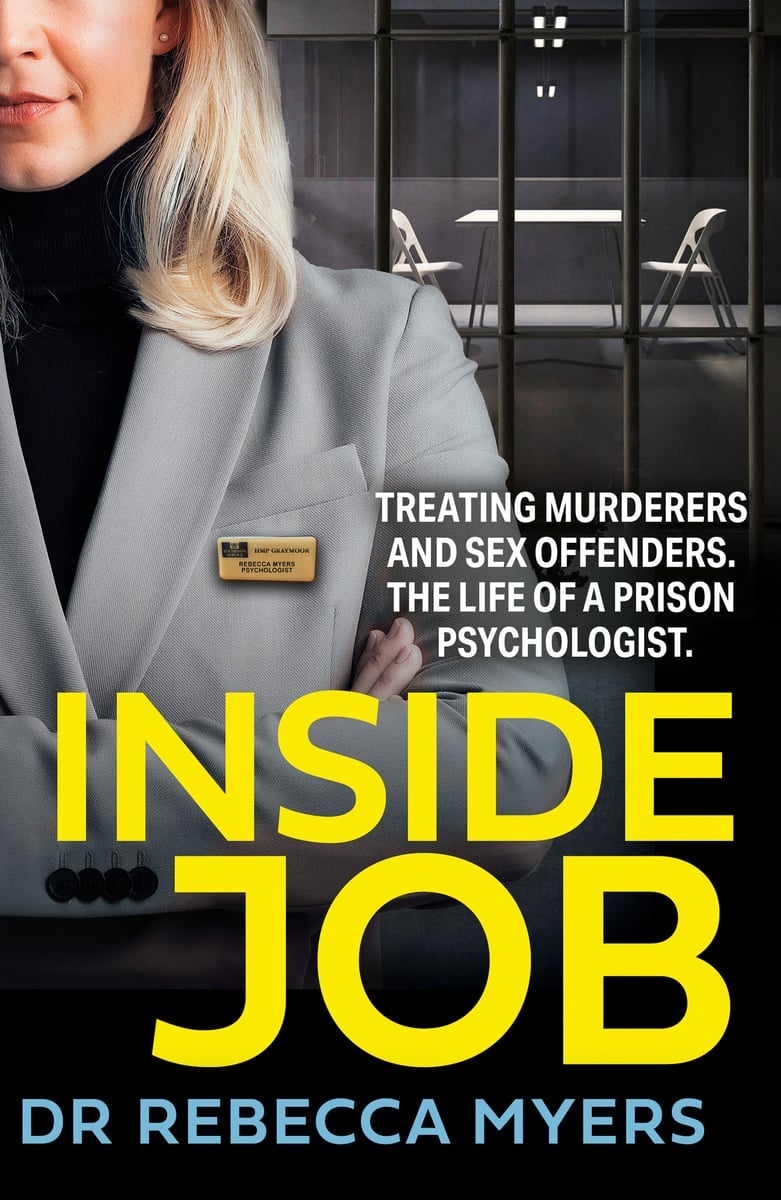

Book extract taken from Inside Job by Dr Rebecca Myers, published by HarperCollins.

My heart is thudding inside my chest like a trapped bird against glass. To my right is an enormous concrete wall capped with a metal tube and, balancing on top, a curling roll of razor wire. To my left is one of the red-brick wings of the maximum-security Graymoor prison, dotted with rows of tiny white barred windows.

The cells. A low wolf-whistle and a shout cut through the drizzle. I cannot see where from, but someone can see me. A man with an Alsatian is patrolling the lonely strip of green at the bottom of the wall. The dog strains on his choker lead, pulling the prison officer along. Both dog and man have their eyes low, searching for contraband thrown over the wall.

We walk down the wide tarmac drag until we reach the arched wooden door of the old prison. I’m with my newly appointed supervisor, Louise, a senior forensic psychologist.

She draws a bunch of oversized keys from the leather pouch on her belt and unlocks the door to reveal a barred gate. It swings heavily inwards to allow us to pass into what is known as the 'Centre' of the prison. I look up, not expecting the tall ceiling.

It’s a domed, circular space and radiating from it like spider’s legs are four wings, four floors high, all encased in cream metal bars and steel mesh.

The first thing that strikes me is the distinctive smell.

An institutional cocktail of unwashed, incarcerated men and boiled vegetables, brewed courtesy of the fusty air circulating through the Victorian prison’s heating and ventilation system. The second thing is the noise. A loud, deep, constant mumble of men talking. No one voice identifiable, rather a current of sound, like a rumbling river.