The Australian government will soon ask voters whether the law should allow same-sex couples to marry in the Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey.

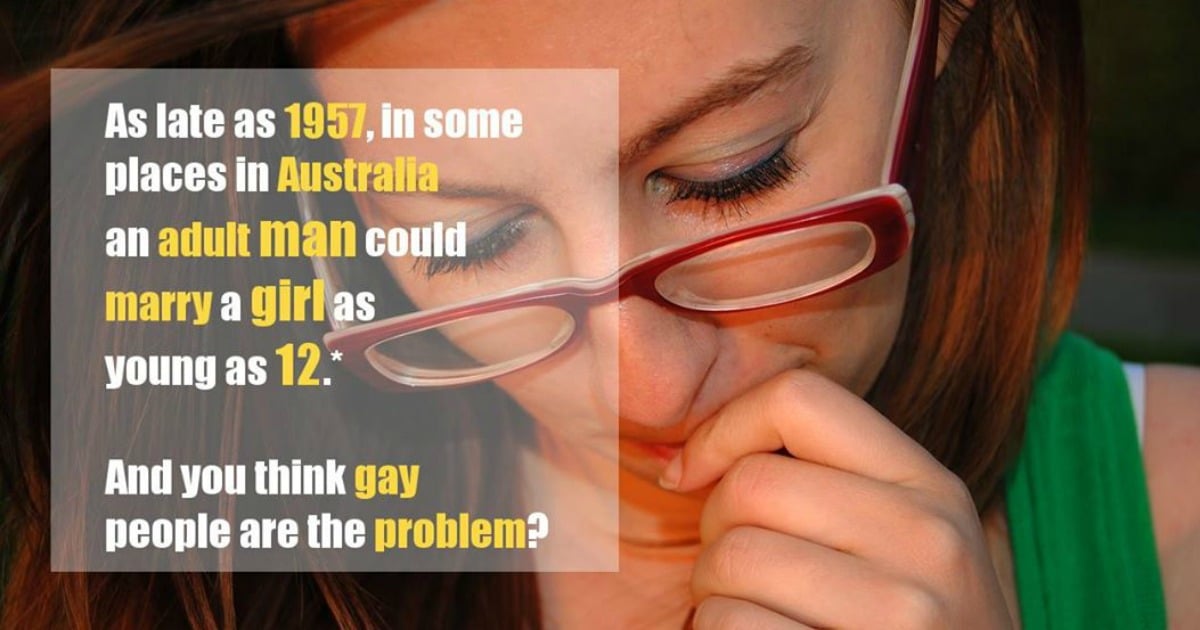

Unfortunately, misinformation persists about the likely impact of amending the Federal Marriage Act if most Australians reply ‘Yes’.

I come to the marriage equality debate with my own biases, knowledge, and experiences.

Professionally, I have a law degree with first-class honours, graduating from the Australian National University with the Prize for Commonwealth Constitutional Law.

For 3 years, I helped to edit an encyclopedia on the High Court, The Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia (2001), and for 7 years I worked with senior lawyers on some high profile cases, including landmark constitutional cases.

As for my personal life, my parents raised me in a strict Roman Catholic household. I dutifully attended church every Sunday until age 38.

I was a member of the Liberal Party of Australia in 1993 and again in 2010.

Against this brief background, I present my responses, as factually as I can, to dispel some of the most misinformed commentary spreading around the Internet and the mainstream media about same-sex marriage in Australia.

Here are nine of the most persistent myths about same-sex marriage in Australia.

Myth 1: ‘Gays already have legal equality!’

In 2008, federal legislative amendments corrected a lot of the legal inequality that lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) people faced in Australia. But those amendments can go only part way while the law denies the legal status of marriage to LGBTI people.

Top Comments

This article does not address one of the most insidious myths of the campaign - that the only reason most people are voting No is because the Yes campaign is bullying people, or to "stick it up" the Yes campaigners for being aggressive.

Firstly, if bullying is a major concern to you please do some research about which groups of people are most likely to commit suicide due to bullying. One of my closest friend from school is gay and the things he endured in his life are horrific. Being punched and called a fag by a total stranger on the train, being bashed when walking down the road, being picked on at school the list goes on. Of course I am not saying I agree with every article written by the Yes campaign, or that all No voters would not empathise with him - but maybe stop and think about why their reaction can be so emotional before you just them as the aggressors,

Secondly if you are only donkey voting or using your vote as an F.U then please rethink your position. We are incredibly fortunate to live in a Democracy such as Australia and the power to vote has a huge amount of responsibility attached to it. There are many ways to voice your disapproval of campaign techniques (by either camp) - however using your vote to effectively stop the marriage equality vote before it has been given a chance in parliament just to "stick it up' someone is irresponsible and an affront to Democracy.

Lastly, I don't even know why I bothered to write all this as I actually don't think people would change their vote based on this and its probably just an excuse to vote No.

Thank you

"The Howard government, with the support of Mark Latham’s Labor Party, put the gender requirement into the Act" now that explains a lot