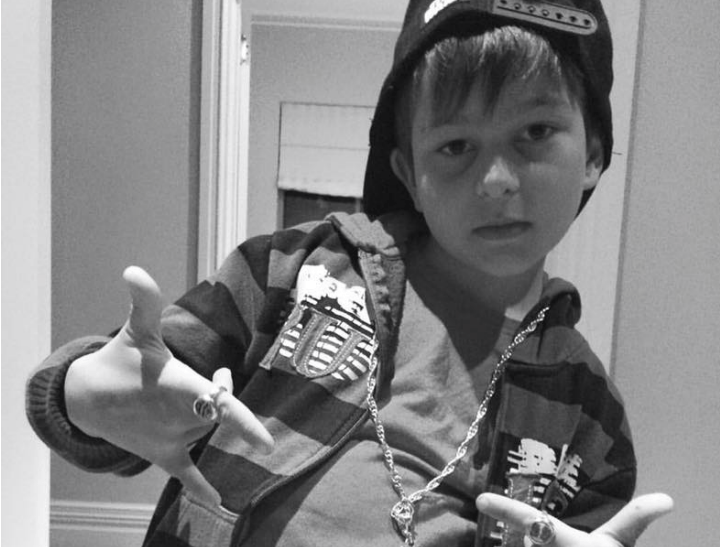

“Because Harrison was born to people of privilege, in this country, at this time in history he is surrounded with social scaffolding built to give him every chance of not only surviving, but thriving.”

On December 4, my son Harrison and I will head into hospital and he’ll receive my kidney in a transplant operation. It’ll be my first major operation and Harrison’s 13th.

There is nothing that has made me more aware of my own privilege than the journey to this big moment in Harrison’s life.

When my wife Rachel and I went to our first pregnancy ultra sound, we discovered our son had a “lower mesodermal defect” that meant all of the amniotic fluid that should have been filling Rachel’s womb was instead trapped inside his bladder, damaging the development of muscles, organs and various body parts. Doctors told us there was no hope of survival, but, after some encouragement, suggested a procedure that would, in their words, increase his chance of life from 0% to 1%.

Top Comments

On the other hand if you think about what would happen if you bring every struggling person from third world into Australia, despite it's kindness and generosity this country won't be able to sustain them all and all those benefits will dissapear quickly, only rich people will have access to such treatments, hospitals and streets will be overcrowded, there won't be enough houses and infrastructure to keep it at the same level. You were lucky to be born here millions of other people are not that lucky but there is nothing you can do about it.

There's a lot you can do for others less fortunate .. the first thing would be to put an end to the delusional self-justification that you are spouting (do you really believe you are powerless to help bring about change). And even if you can't bring yourself to consider the plight of people born overseas, maybe you could consider those born here in Australia who for whatever reason find themselves in a less than privileged position. Take off the rose-coloured glasses and do what you can, no matter how small or insignificant it may be - I can't imagine you would ever regret it!

Has nothing to do with being white and middle class and everything to do with being Australian. I have had a kidney trandplant due to my husbands donation without his gift i would still be on dialysis and should i have been born in another country i may not be here to type this. But still there are treatments for other illness in this country which are not funded so you also have to be lucky enough to have an issue that is funded.