As your fingers scroll down the screen, she catches your eye.

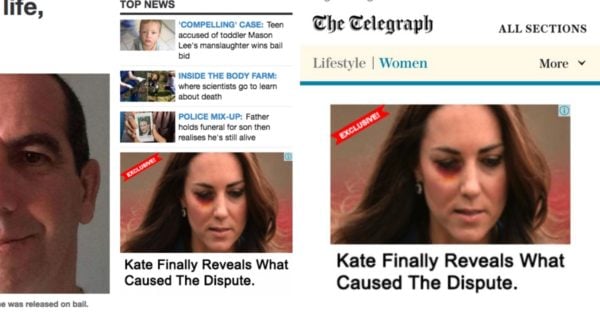

Her head is down, her eyes cast to the side, a black eye covering a good portion of her face. If you look a little closer, you notice it’s not just anyone’s eye, and it’s not just anyone’s face.

It’s Kate Middleton.

The text below the advertisement reads: Kate Finally Reveals What Caused The Dispute.

Kate, black eye, the mention of a dispute. Your mind moves. Domestic violence, perhaps?

You click through the ad, and you stumble upon an article, or so it purports to be.

“Princess Kate Middleton Will Spend Time Away From the Royal Family To Campaign For Breakthrough Skincare Line!” says the headline, with the article sitting on a website that looks a lot like PEOPLE Magazine, though it’s not. There are no mentions of black eyes or disputes and the implication of domestic violence? All but forgotten.

Top Comments

That's an appalling thing to do to anyone, esp such a famous couple. What were they thinking? Prince William and Kate should sue.

Absolutely disgusting!