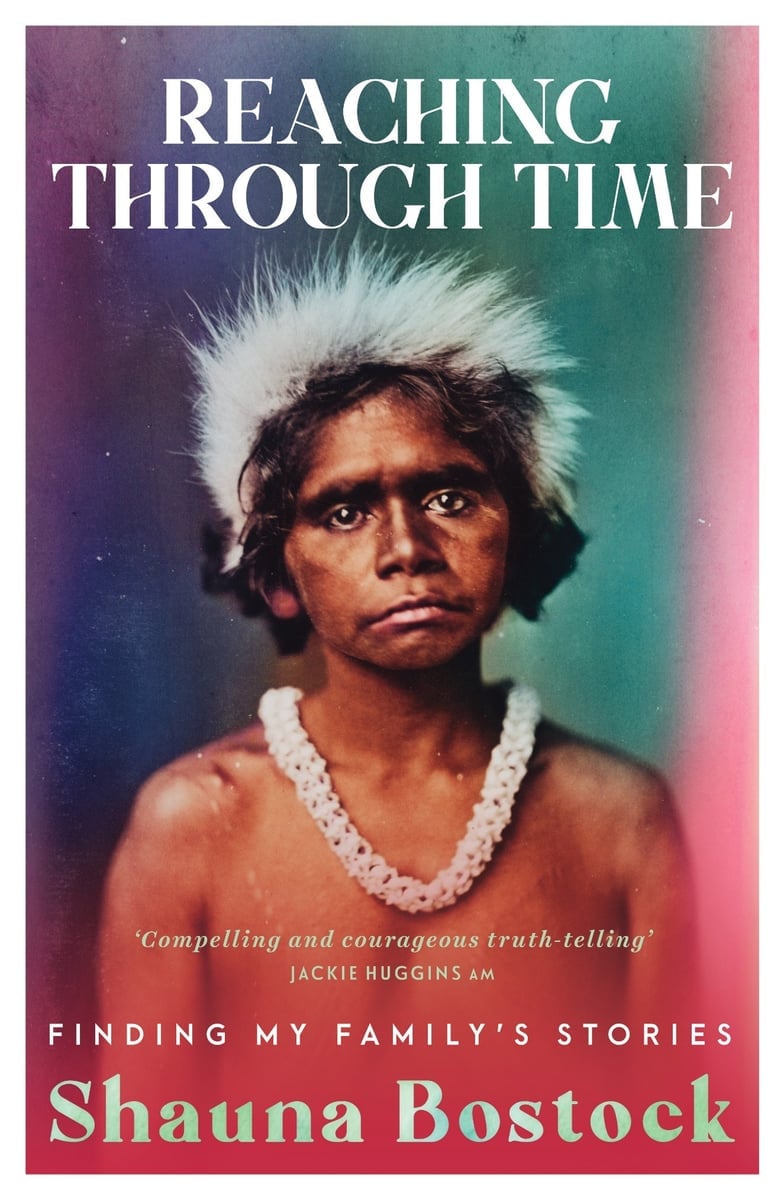

I am Bundjalung. I am an Aboriginal Australian and I come from Bundjalung Country on the southern border region of Queensland and in the Northern Rivers region of New South Wales, on Australia’s east coast.

In the Tweed River valley, a sacred mountain called Wollumbin stands majestically as the first place on mainland Australia to receive the sun’s rays each day. It is my family’s ancestral home.

My ancestors woke up in that sunshine, drank from crystal-clear streams, hunted game, were guardians of the forests and the mountains, and maintained and preserved sacred sites of Earth magic.

Watch: What Country means to Indigenous people. Story continues after video.

As an urban Aboriginal woman who lives in the present, I yearned to connect with my ancestors from the past, learn their history and tell their stories. I have travelled on a long and exhausting journey, for over a decade, to find a way to bridge these worlds.

Why don’t you know?

I vividly remember how shocked my fellow student Lynda looked, how the mortification in her voice made her sudden question sound more like an interrogation rather than the urgent, truth-seeking inquiry that she intended. She whacked me on my shoulder and gasped, ‘Did you know this!’ I responded sadly, ‘Yes . . . Why don’t you know?’

Top Comments