Just before 9am on July 30, 2002, Karen Boes walked out of her Michigan home, jumped in her car and went to visit her then-husband’s work.

After popping by, she headed down to a local Burger King, picked up an iced tea and met a friend for a spot of shopping.

As she ran her errands, drunk her tea and socialised, her 14-year-old daughter Robin perished in the family home, engulfed by flames that spread with ferocious intensity. The fire – one that quickly made its way to Robin’s bedroom from the hallway outside her door – was spotted just five minutes after Karen left the house.

Karen was the immediate, and only, suspect.

After sitting through 16 hours of videotaped interrogation, she incriminated herself, police said. Small hints placed her at the scene of the crime, before the fire took hold.

Or so they say.

Karen Boes, the centre of a new Netflix documentary The Confession Tapes, believes the reason she has served 15 years for her daughter’s death centres on a confession she never meant to give.

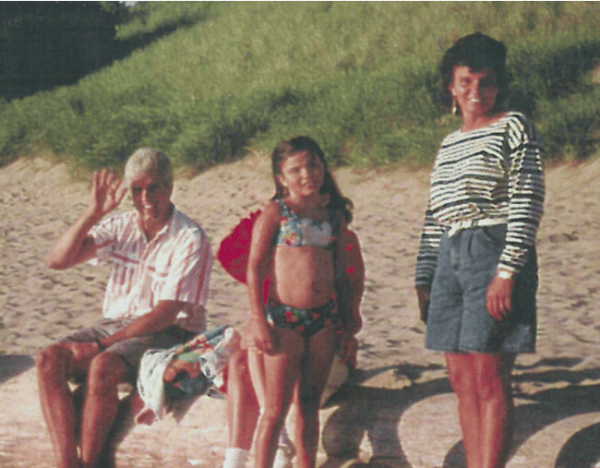

“I was falsely accused and convicted of the murder of my precious 14-year-old daughter, Robin Lynn Boes,” the 61-year-old said in a letter sent from prison, according to Michigan local news.

“The state had absolutely NO evidence against me and we were able to solidly establish that I was with a friend shopping in a city 30 miles away at the onset of the fire that took my daughter’s life,” she wrote.

In statements made while testifying, Boes said after hours and hours and hours of interrogations, she began to question if she was going slightly “insane”.