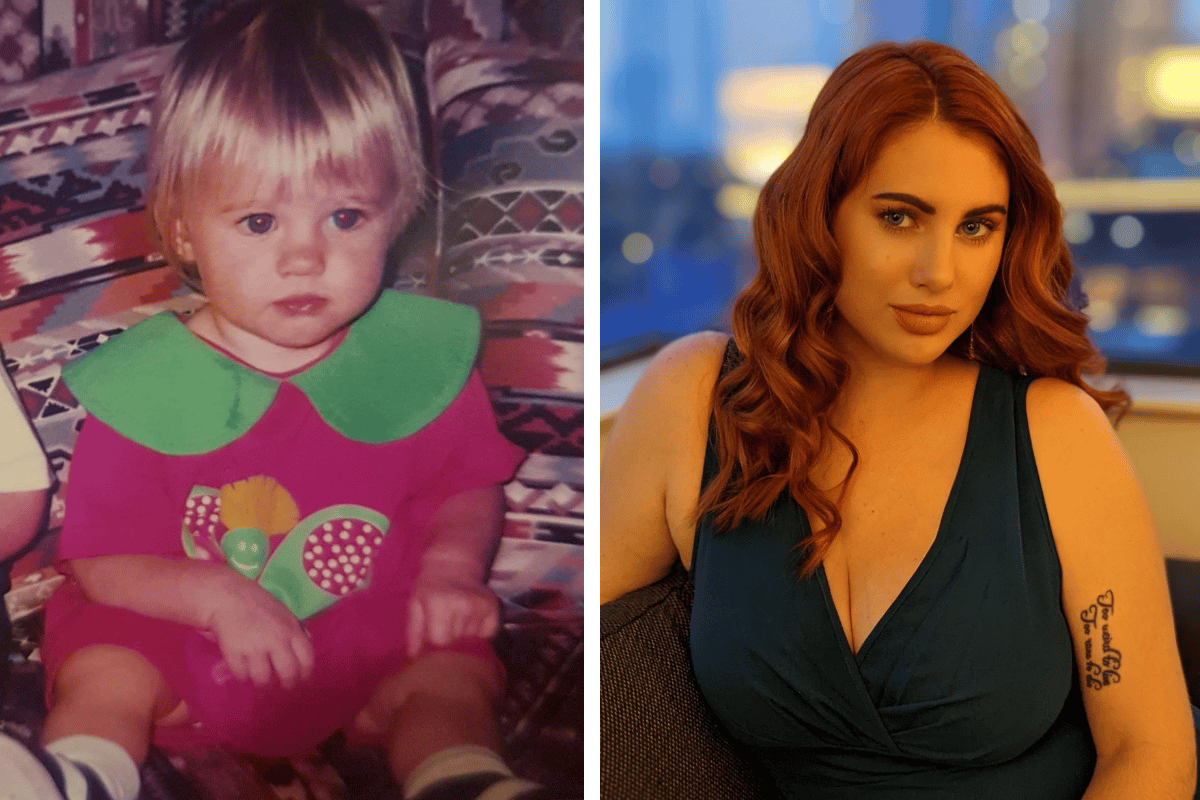

Emily Fae has always been interested in her family’s history. During the COVID lockdowns in early 2020, when she was stuck at home with her toddler, she decided to pay for an online DNA test.

“Finding out more about my ancestry was exciting to me,” Emily tells Mamamia.

“My best friend was interested too, so we both did the test and sent off our samples at the same time. Six weeks later, I got my results.”

At first, Emily, then 27, says everything was normal, apart from a few mysterious discrepancies.

Watch: Amy Tam on SBS Insight in 2020 talks about her experience of being donor conceived. Post continues after video.

“The results said I was half Welsh which was weird as I knew my dad’s family was from Cornwall, not Wales. Also, no one had my dad’s surname but it didn’t occur to me there was anything wrong. I just thought it was cool. Then I received a direct message on Instagram from a teenager in Victoria who said we were related.”

Emily cross checked the results with Ancestry DNA, which confirmed the person was either a first cousin or half sibling.

“I was like, ‘wow’ and I was excited to find out I had a new relative. She told me she was donor conceived and so I thought my dad or one of my uncle’s must have donated their sperm at some point in the past. It was about 10 or 11pm at night and I called up my mum to tell her my news and it was that phone call that changed my life forever.”

Top Comments