“There’s a ghastly smell like decomposing mummies,” Olive Haynes wrote in a letter to her sister.

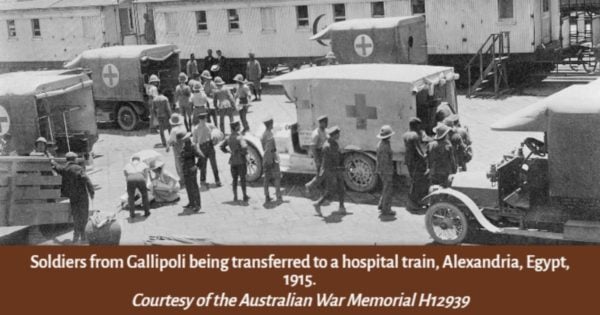

Haynes was writing from Alexandria, Egypt, where casualties from the Gallipoli landings were being ferried in by the thousands.

Some no longer had recognisable faces, their jaws or noses blown off by grenades, and others wore multiple bullets, shot several times by machine guns.

Australia had barely become a nation and already we were fighting for it. Or so we thought.

Listen: Michael Ware speaks to Meshel Laurie about being captured by Isis soldiers. Post continues below.

We know the story of the men who arrived on the shores of Gallipoli, on the 25th of April 1915, knowing nothing of the trap they’d stumbled into.

We know the story of the 15-year-old boys, so eager for an adventure they lied about their age.

We know the story of the nonsensical British orders, the cost of which was 8709 Australian lives, and 2701 New Zealander lives. In total, the Gallipoli campaign took the lives of 44000.

That, as they say, is history.

But what about herstory?

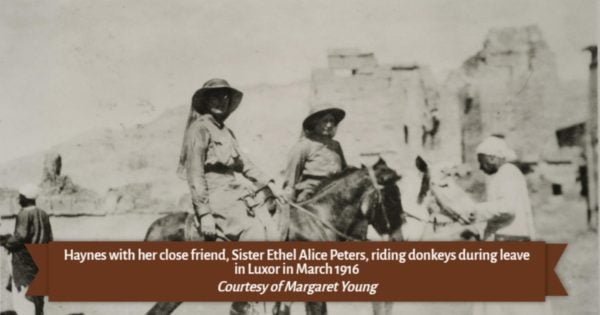

Born in 1888 in Adelaide, Haynes loved reading, painting, music and had great interest in social issues as well as the welfare of others. It seemed a natural fit that in 1909 she began training as a nurse – despite her parents’ attempts to dissuade her. In August 1914, at 26, Haynes enlisted in the Australian Army Nursing Service.

Top Comments

True heroine should be remembered everyday.

Think you meant heroine :-) heroin kind of changes the point lol

Unfortunatley spell check doesn't always work and

where not all perfect like you.

Woah girl, I didn't mean to offend you. Just found it amusing. And I'm not perfect, far from it but I am capable of having a chuckle.

When I was in high school, we were required to do an assignment on service people during ww2. I researched and found a former nurse and her soldier husband who had been a POW in Changi. I visited them in their home to interview them. It was the most fascinating and inspiring hour I've spent with someone. The stories were heartbreaking, joyous and bleak at times. She told me about Vivian bullwinkle who was a personal friend of hers and how she almost ended up on that ship. Stories like olives and vivians and (I think her name was June) continue to highlight the strength of women and the contributions they made which often goes ignored. So wonderful to see their stories being featured a lot more now. Thank you for sharing