Earlier this month, a designer from Germany created a pair of shorts with the aim of protecting women from possible sex attacks while they are out jogging.

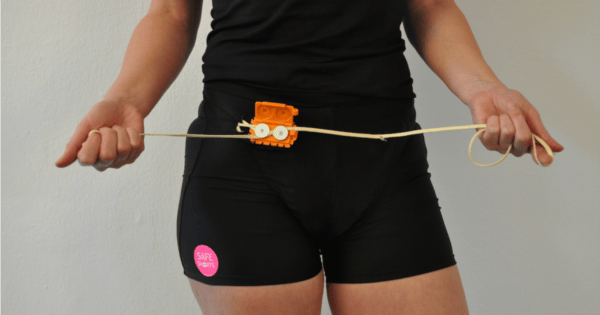

Complete with a lock for women’s intimate areas and an alarm to sound lest a stranger approaches, the shorts are made of the same material as bullet-proof vests and can only be cut by attackers. You can pick them up for about AU$215.

And if as you read that you felt a rising sense of unease, you’d be understood, if not totally exonerated.

In a world that consistently enables attackers by questioning the victims, and one where rape culture remains insidious, why are we spending our money, time and energy on things that don’t work towards prevention?

Why, as you have no doubt heard argued time and time again, is the onus on women to not get assaulted rather than on the men to not do the assaulting?

At the crux of it, of course, are those underlying ideas. But what happens when the debate grows in complexity?

Business graduate, Sandra Seilz, decided to invent the trousers after she was attacked by three drunk men when she was jogging in the woods.