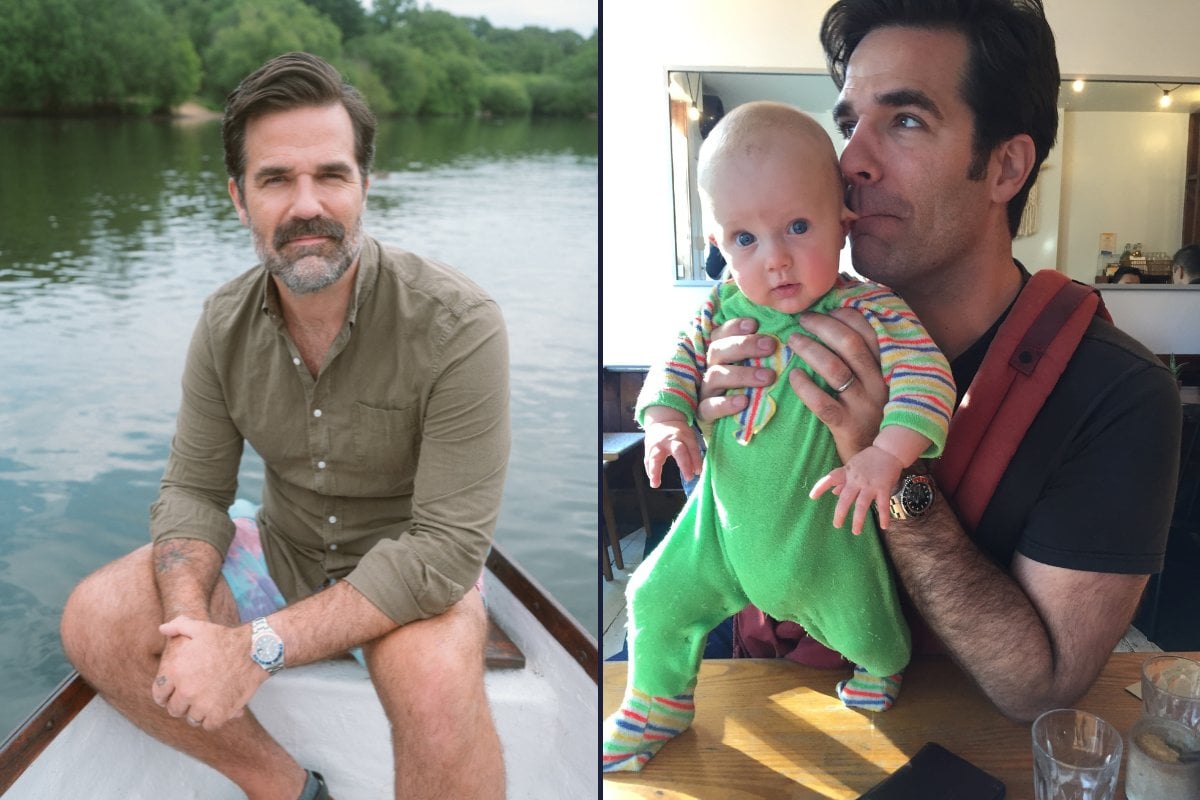

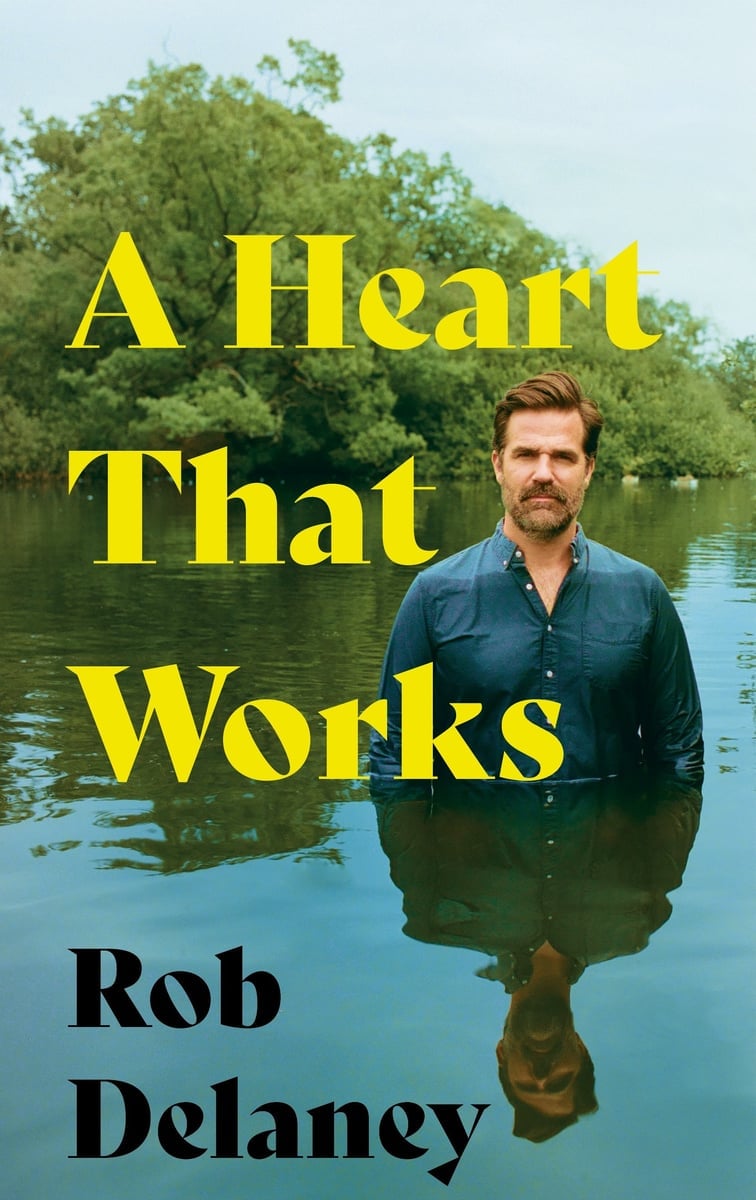

The following is an excerpt from A Heart That Works by Rob Delaney, a visceral and deeply personal memoir by the star of the Amazon Prime series Catastrophe, about love, loss, and fatherhood.

I swim most days now in a pond near our house. There are ponds of various sizes scattered around London, and I’m lucky to live near enough to a couple of them that I can run or cycle a short distance and get wet in a natural body of water. My favourite pond is managed by the city, and if you attend a short briefing, give them eight pounds, and put on an orange swim cap, they let you have at it. It’s roughly one mile across and ringed by tower blocks and newer, shinier residential buildings. One time, a heron carrying a dead frog in its mouth flew over me as I swam. I went home and told my four-year-old, and he started crying and told me that the frog was his friend.

Had you told me even five years ago that I would be a habitual swimmer in a body of water that was not the ocean, I wouldn’t have believed you. I grew up next to the ocean, at the beach as often as possible, or sailing around the little islands off Marblehead, Massachusetts, in a tiny little sailing boat called a Widgeon. So the ocean was not a problem for me, but I’ve spent most of my life afraid of lakes and ponds. Frankly, I wasn’t even crazy about pools.

The way I intellectualised it was that if something killed me in the ocean, I would understand what had happened; there would be no mystery. My autopsy would read ‘shark attack’ or ‘run down by drunken teenager in a Boston Whaler and hacked apart by engine blades’. It would be awful, but anyone who read the report would understand what had happened. Whereas if I met my end in a lake or pond, that would AT BEST mean that sentient vines had reached up from the pond floor and coiled around my thighs and waist and pulled me down, not even allowing me to scream because they’d tightened around my throat and crushed my larynx. Or, more likely, that the gas bloated zombie-corpse of a murdered postman had slipped a rusty handcuff around my ankle and was going to yank me down and make me be his wife for eternity.

Top Comments