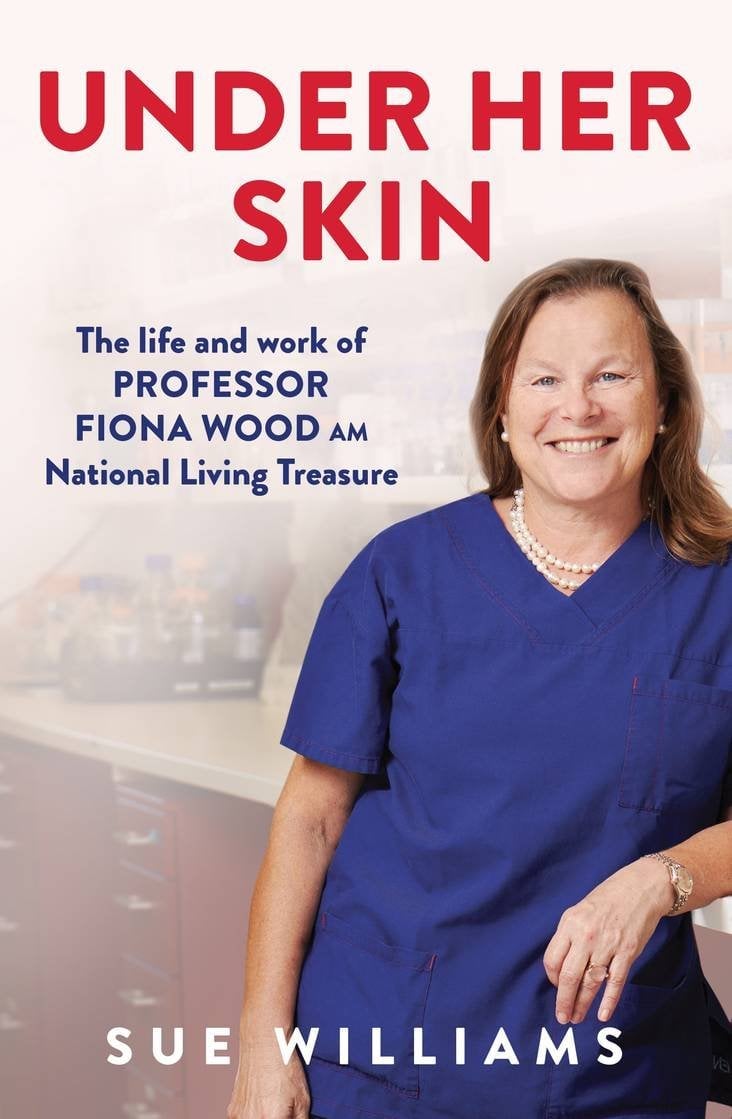

The following is an excerpt from Under Her Skin by Sue Williams, the remarkable story of Professor Fiona Wood AM whose groundbreaking research and technology development has changed the lives of burns patients.

It was the biggest ever peacetime emergency evacuation of Australians from overseas, and the largest air evacuation since the Vietnam War, with more than 100 patients—most with horrendous burns and terrible injuries, and many fighting for their very lives—airlifted to safety.

But what made the biggest impression on Fiona that day was something much more intimate. ‘The thing that overwhelmed me when I saw the patients was the look of relief on their faces,’ she says quietly. ‘That’s the one image I’ll remember forever. They were home: they felt safe; they felt secure. But we knew their battles had only just begun, and we got straight to work.’

With most foreigners now being extracted, Sanglah Hospital and clinics in the neighbouring areas were better able to cope with the smaller number of Indonesian casualties. Meanwhile, eleven patients arrived in Perth direct from Bali, among them 29-year-old Sydneysider Jodie O’Shea, the young woman Dr Vij Vijayasekaran had been so impressed with. Her burns had, back then, looked the most severe at 92 per cent, but her demeanour, her humour and her obvious courage had made Vij hope against hope that she’d be able to beat the odds. On her arrival in Perth, everyone immediately understood why. The emergency staff were all similarly charmed by her smiles, her polite manner and her grace, and were devastated to realise she was unlikely to make it; her injuries were just too overwhelming. But when she died within a few hours, it was, at least, in her mother’s arms.