The following is an extract from Vanished: The true stories from families of Australian missing people, by Nicole Morris, available via Big Sky Publishing.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains photos of people who have died.

It would be distressing enough to have a missing brother for the last three decades. But what if you thought his body might have been found, and no-one will tell you whether or not that's true?

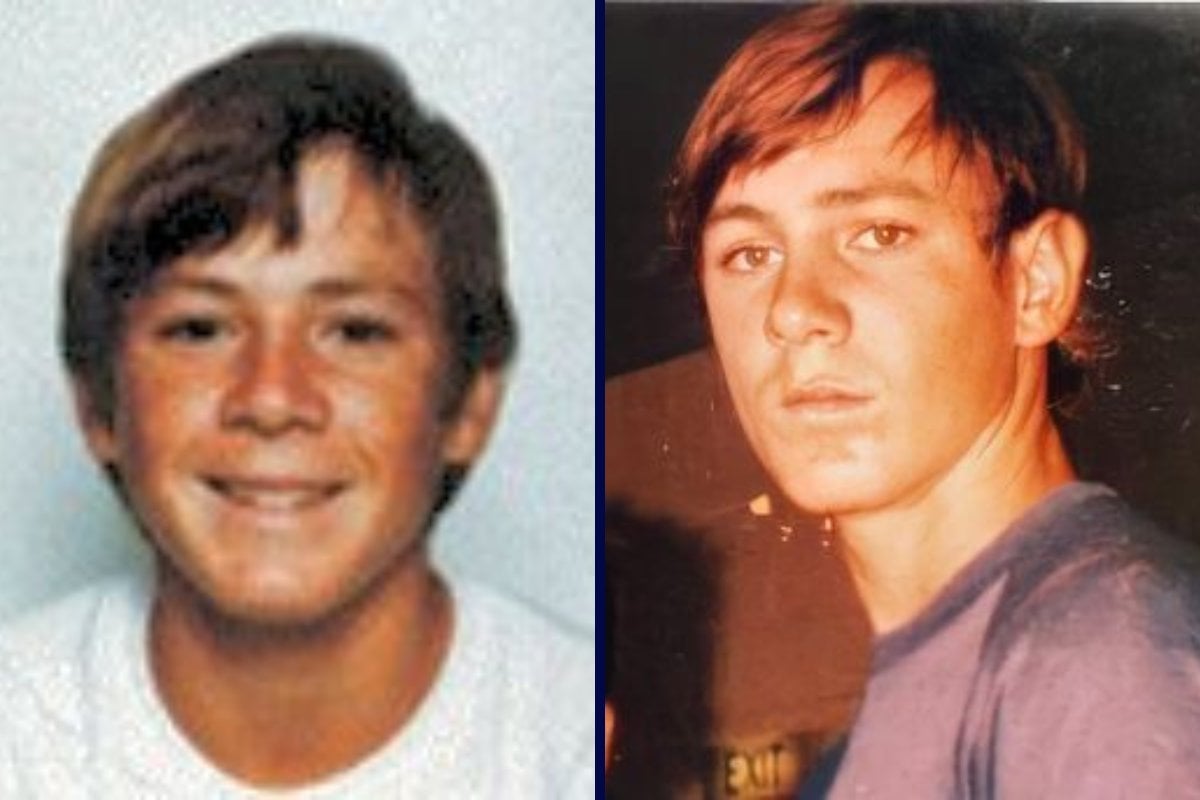

That’s the situation facing brother and sister Murray and Susan Lawson. Their brother Norman was last seen in 1986, when he was just sixteen years old. In 1990 a body was found, with a gunshot wound to the head, but since that time various government departments have told the Lawson family conflicting information about whether this body is Norman. They’ve now been waiting more than 30 years for that answer.

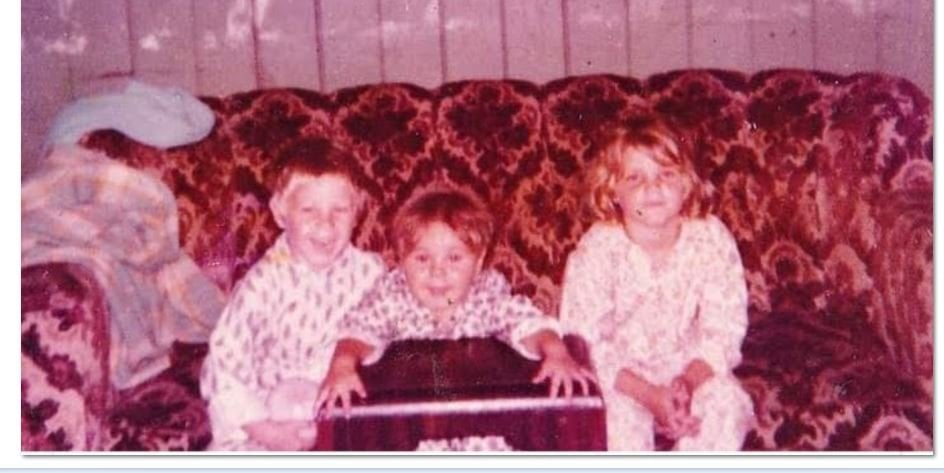

Norman Lawson was born in Melbourne. Older sister Susan and younger brother Murray completed the Lawson children, but they were not a happy family. Murray and Sue speak about constant fights between their parents, which resulted in them frequently moving. Their parents separated and Murray lived with his mother, while Norman and Susan stayed with their father, Henry. ‘I was passed round the family,’ says Murray. ‘It’s very hard to talk about. I had an abusive childhood. We were all together when we were younger, but Mum kept taking me away, and we ended up in the Northern Territory.’

His father, Henry, was Aboriginal and his mum was white. Murray recalls people were critical of his parents’ mixed marriage, making their childhood difficult.