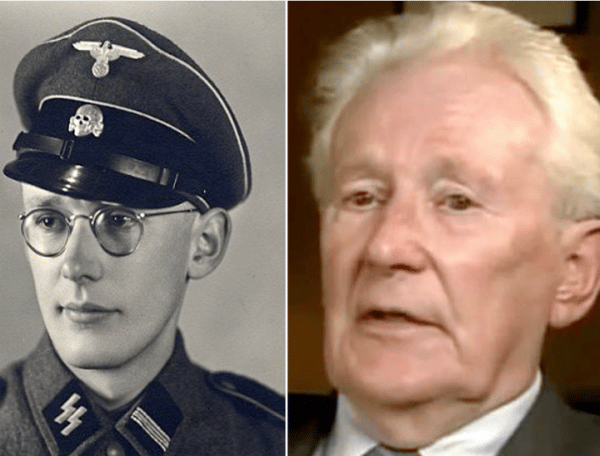

This week a Nazi officer was convicted of 300,000 counts of being an accessory to murder and sentenced to four years in prison for his involvement as the “accountant of Auschwitz”.

Oskar Groening is now 94 years old. He was 23 when he counted and sorted the belongings of Jews brought to Auschwitz. The proceeds were used to fund the Nazi campaign.

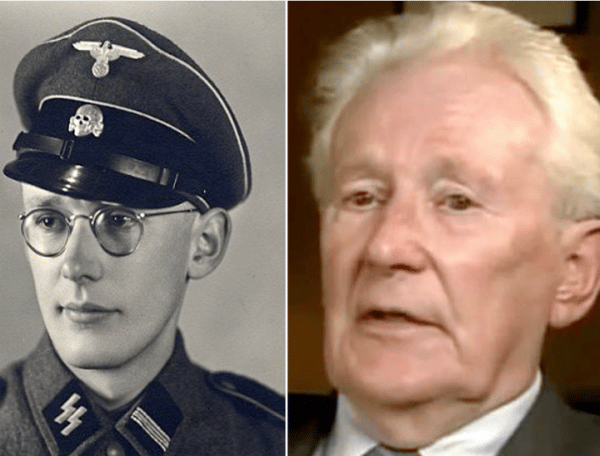

And this week, I was again reminded of the gross – truly gross – injustice my grandmother, an Auschwitz survivor, lived with for her entire life.

Each time one of these sentences make the news, I ask myself whether I feel rage towards these Nazis. Whether I think they deserve to live the last few years of their life in prison (where conditions would be better than those they created for my grandmother in Auschwitz). Whether I pity their stupid, youthful decision to blindly follow a sadistic cause.

Top Comments