This article deals with an account of infant loss that could be triggering for some readers. For support, please call Red Nose Grief and Loss on 1300 308 307.

People often say that you don’t realise how lucky you are. I did.

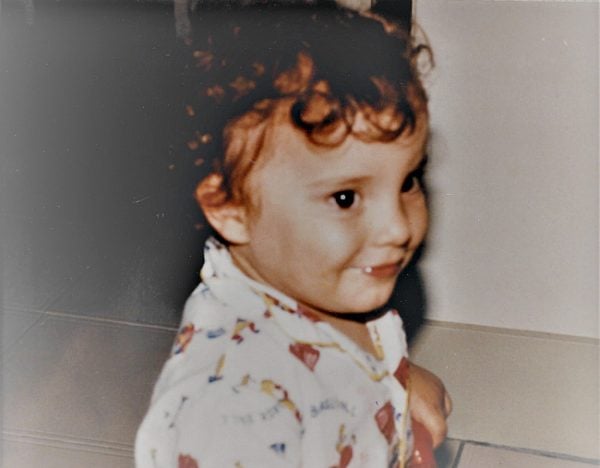

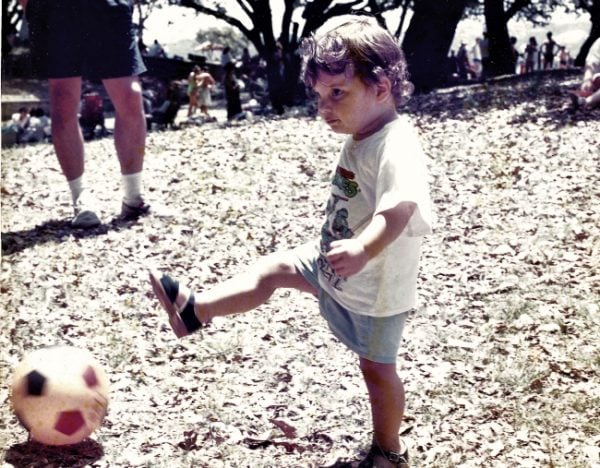

I did, because after losing a little girl late in pregnancy and then, a year later, being told that my beautiful three-day-old baby girl, Charlotte, was probably not “going to last the day out”, I realised with acute clarity that I was one lucky mum to be here, almost two years later, with three beautiful children – four-year-old Alexander and almost two-year-old twins, Damien and Charlotte.

And then the world shook.

I woke up on Thursday March 14, 1991, to my beautiful Damien, face down in his cot. Dead. The horror, the chaos, the falling to the bottom of the earth. The searing pain and the absolute unreality of that morning and countless mornings thereafter are indescribable. It is a place I prefer not to go because it makes my life unbearable.

And that is, I think, how one copes with immense grief. You learn to cover it in your heart, day by day, layer by layer. You learn not to visit it, because when you do it robs you of your breath.

It is wrong to say that “we are only given what we can manage”, because we don’t manage. Parents like us move from one day to the next, fulfilling the minutia of life ensuring our living children, if we are lucky enough to have them, are kept safe and healthy.