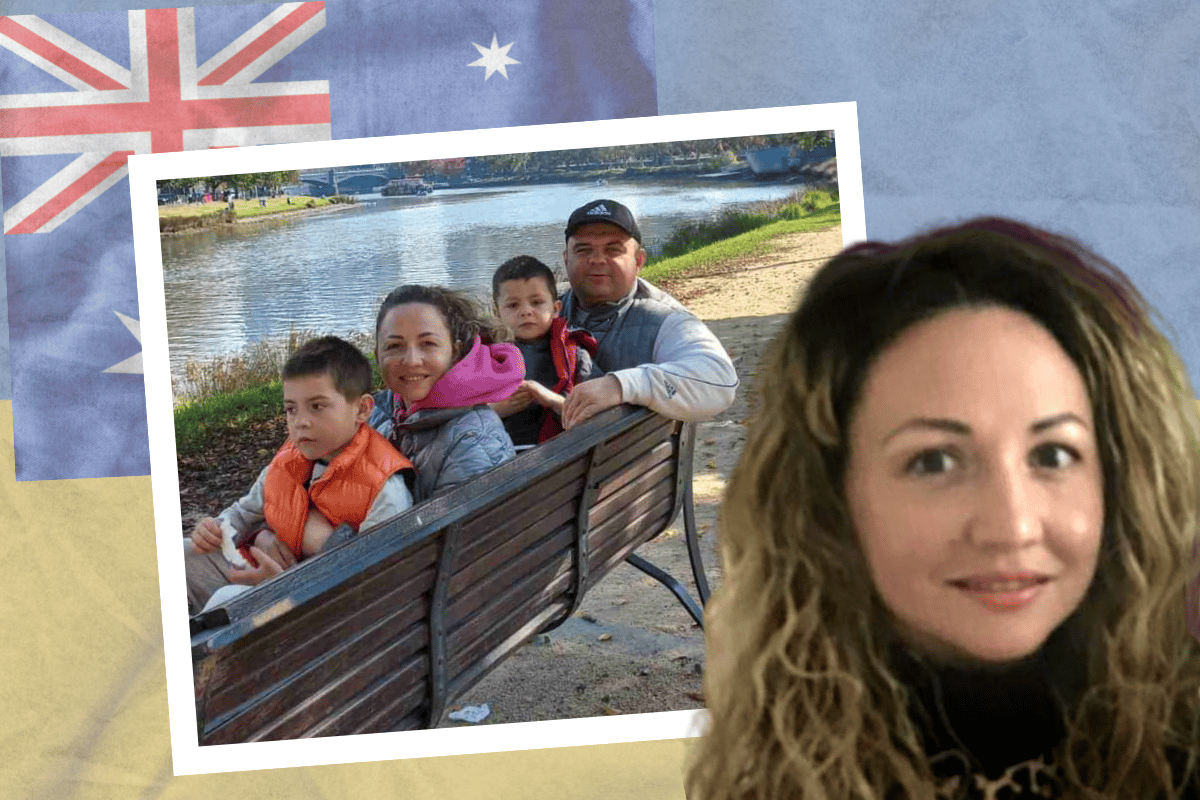

As Yulia Konokhovych flung open the front door of her unassuming 1950s brick veneer in Melbourne’s south-east, I was met with her kind smile.

The mid-30s mother of two has her hair gathered into a neat plait. Her top eyelids are each lined with a simple black stroke.

“Please, come in,” she implores, a melodic lilt to her accent.

She thanks me for the continental pastries I’ve brought and ushers me into the living room, before disappearing into the kitchen.

Yulia's warmth stands starkly against the sparseness of the space: Two small couches face each other upon the naked floorboards in an otherwise empty room. A single lamp sits on the mantel above the wall-mounted gas heater, impossibly tasked with warming the old bones of the house.

Sweet buns cut into thick wodges await on the little dining table nearby.

“Please sit,” she beckons, reappearing with cups brimming with black tea atop saucers and carefully folded serviettes.

Yulia, her husband Mike Kyrylovych, and their two sons - aged five and four - are refugees from Ukraine.

They have only been in Australia for one month. And yesterday, after weeks of living with a family who generously took them in, they moved here, to a rented home of their own.

“My English maybe not so good,” says Yulia apologetically, “But I’ll tell you.”

“This is our story.”