The Call came on a sunny afternoon in spring. Every parent dreads The Call, a sombre voice informing you that something unspeakable has happened to the precious being you’ve used your every trick to protect since they were just a clump of multiplying cells. But when your child has told you countless times that she wants to die, and on several occasions has very nearly made that happen, I think you dread it more.

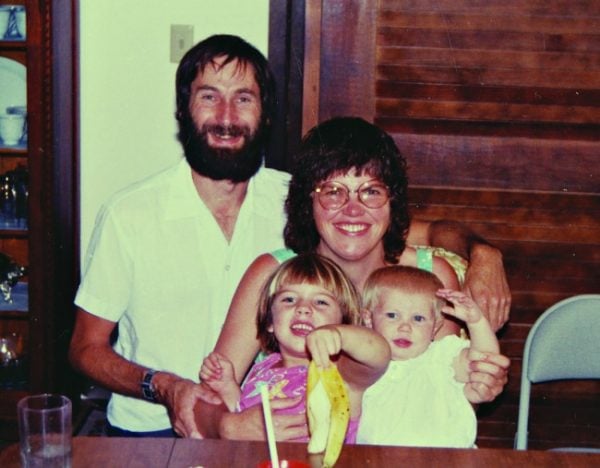

I was already on my mobile, chatting to a friend, out in our unruly backyard. Thirty years before, when John and I jauntily referred to ourselves as ‘young homebuyers on the march’, we were thrilled to find this big block with its many trees and a house full of light, in a little suburb called Oak Park in the northern suburbs of Melbourne.

The friend I was listening to was deeply upset about a row she’d had with another friend of ours, and she needed to vent. That’s when the two little beeps came, plonked in the middle of one of my friend’s sentences. I reminded myself not to panic. Over the last few months I’d been practising the discipline of not reacting instantly to Anna’s dramas.

So I waited till the conversation came to a natural end, then I checked my missed calls. Voicemail. I pressed the green light, the one in the shape of an old-fashioned telephone receiver. Easy. No warning that a tiny light would slice my life in two, dividing it neatly between Before and After.

Top Comments

It sounds like the same thing in the USA. There is no place for mentally ill people to go to unless they are a danger to themself or society, even if they are having a psychotic episode. It seems the bar is set very high for someone to get help in the U.S. And, in the U.S., a patient is only involuntarily committed if they commit a violent crime. Like Australia, they can check themselves out of the facility. I honestly don't understand why it is like that.