Warning: This article discusses family violence and may not be suitable for all readers.

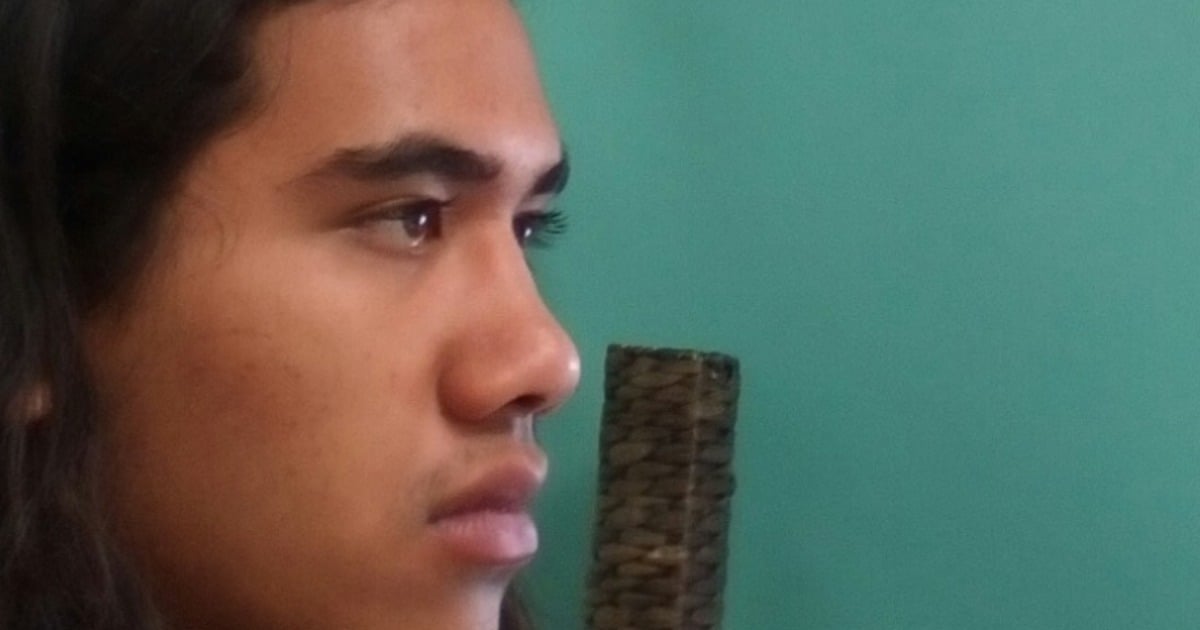

Hours before police arrived at a triple murder in Ellenbrook, a crime scene an officer described as “potentially the most horrific” he had ever been called to, 19-year-old Teancum Vernon Petersen-Crofts walked into a public hospital in Perth.

He presented at the emergency department on Saturday night in a “psychotic state”, AAP reports, but it’s believed he was later turned away.

In the early hours of the following morning, he would allegedly kill 48-year-old mother Michelle Petersen, her eight-year-old son Rua, and her 15-year-old daughter Bella.

After being charged with the murders on Monday, and appearing in court where he had what witnesses described as a “bizarre outburst,” where he spoke “confusingly over the magistrate,” Petersen-Crofts was remanded to a psychiatric facility at Graylands Hospital.

WAtoday reports that despite the 19-year-old’s “erratic behaviour” on Saturday night, when he attended St John of God Midland hospital, his condition was not considered to be a ‘medical problem’. It is also understood police were involved, but when contacted for comment, WA Police said they would not be confirming details in relation to the circumstances leading up to the deaths, as the matter is now before the courts.

Top Comments

They dismantled the residential care facilities back in the 70s and 80s because these people were seen to have a right to autonomy. All that happened is now they live on the streets and there is no place for them except in prison, in hospital (under-funded and ill-equipped) or with long-suffering family. This was a poor policy decision.

The mental health system is broken! There is no help for people in crisis! It's all put back onto the families to source their own resources for help, if it is available! There is no doubt in my mind that we are in a critical situation that is only going to get worse if there is not something done soon! Families are at breaking point!