In 1999, we weren’t quite the cynics we are today. The ability to separate fact from fiction is quite literally in our pockets now; a search, swipe, scroll away.

But 20 years ago, there was a brief cultural moment in which we teetered on the edge of the internet age, a moment in which two filmmakers were able to create a horror film on a $60,000 budget which would leech into the cult movie canon and go on to rake in $250 million.

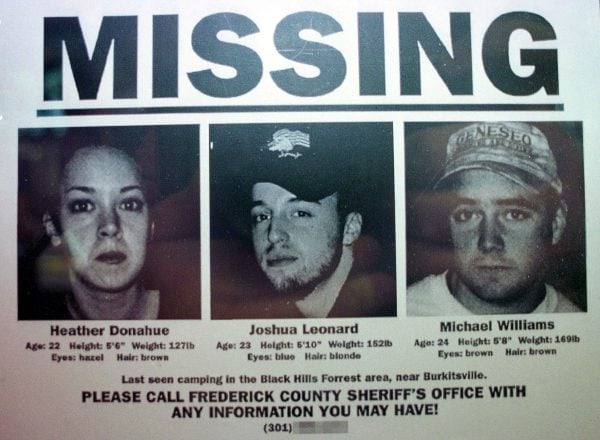

The Blair Witch Project asked us to suspend our disbelief and buy into a supernatural storyline in which a trio of documentary makers ventured into the woods near Burkittsville in the US state of Maryland to investigate a local legend. It’s their footage, found a year after they vanish, that we’re told we’re watching.

The shaky hand-held camera work. The heavy, tearful breaths of the panicked group. The haunting sounds echoing through the trees. Now iconic (and heavily parodied) movie-making moments that pioneered the found-footage genre.

But it’s not just the movie itself that meant countless viewers were prepared to believe what they saw. It’s the legend that masterminds Eduardo Sánchez and Daniel Myrick created behind it.

Top Comments

I saw this movie the night that it came out. I hadn't ever believed it was real and that I was watching a documentary, but it was the very first movie I've ever been properly scared in.

The final shot where the guy is standing in the corner and you know the woman is about to be killed sent a rush of terror all the way up to my face.

still remember that final shot vividly - getting goosebumps just thinking about it!

I found it scary / creepy when I watched it. As you say, especially that final scene.

I did a bit of reading on 'conspiracy theories' about it, apparently, it was all a plan for the 2 guys to kill the girls. It's quite convincing, but you'd have to think they had plenty of time to do it before the final scene.

I know! That ending still sends shivers down my spine! I saw it twice when it came out. It was so scary. I knew it wasn't real, but I had been so excited for it, having seen the pretend doco they put on tv a few months earlier. I remember having debates with friends who were convinced the whole thing was 100% truth!

I know what you mean. That final shot freaked me out so much I've not watched it since