Content warning: This post contains images and details of starvation some readers may find triggering.

In early 1944, with WWII grinding on, a call went out for healthy young American men who were willing to starve themselves.

The men asked to volunteer were all conscientious objectors. They had refused to fight in the war, but plenty of them were willing to suffer to help others. Hundreds put themselves forward to take part in the experiment, which was aimed at finding the most effective ways to help starving people once the war was over. Marshall Sutton, a Quaker, was one of them.

“I wanted to do something that had a little more punch to it,” Sutton said in 2014. “I wanted to risk my life in some way and be of service.”

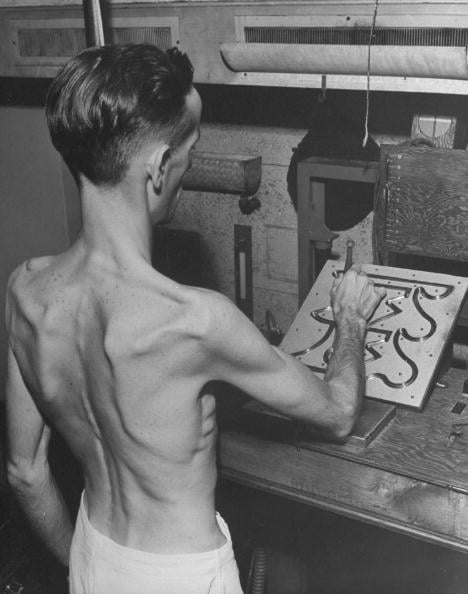

Thirty-six men were chosen for the experiment, which was led by physiologist Ancel Keys at the University of Minnesota. For the first three months, they were given a normal diet, including bacon, eggs, roast beef, mashed potatoes and chocolate sundaes, totalling 3200 calories a day. Then, for the next six months, their diet was cut to a semi-starvation level of 1560 calories a day. Their meals were bland, mostly bread and vegetables such as potatoes, turnips and cabbage.

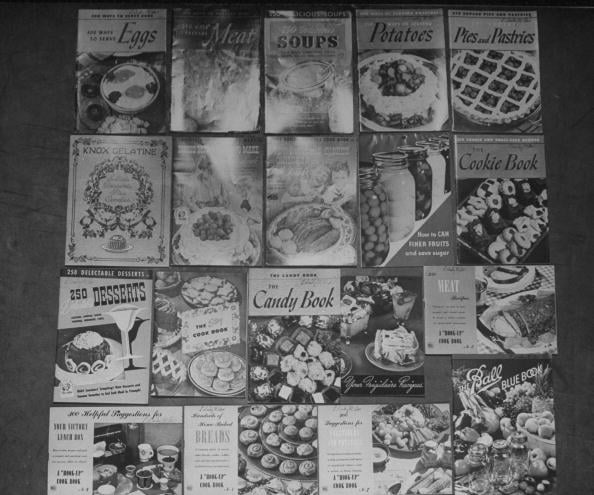

The changes in the men were dramatic. For starters, they became obsessed with food, thinking and talking about it endlessly. They lingered over their meals – playing with their food, mixing it together in strange combinations, or holding mouthfuls for a long time before swallowing. Some collected recipes.

Top Comments

You don't mention why they were doing these experiments.

They knew that after the war ended there would be men all over who were malnourished during the war. They needed to find out what was the best way to fatten them up again.

Letting them eat as much as they want? Restricting their intake so they didn't make themselves sick? Did they require vitamin supplements?

It was important work, and it just goes to show that even though they were contentious objectors they were still prepared to go to great lengths to help their country.