The following discusses domestic violence, which may be distressing for some readers.

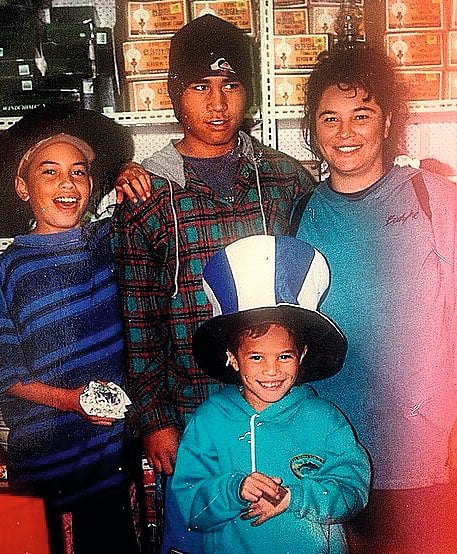

Most people only know the latest chapters of Stan Walker's story: his victory in the final season of Australian Idol in 2009, his subsequent chart success, even his 2017 stomach cancer diagnosis.

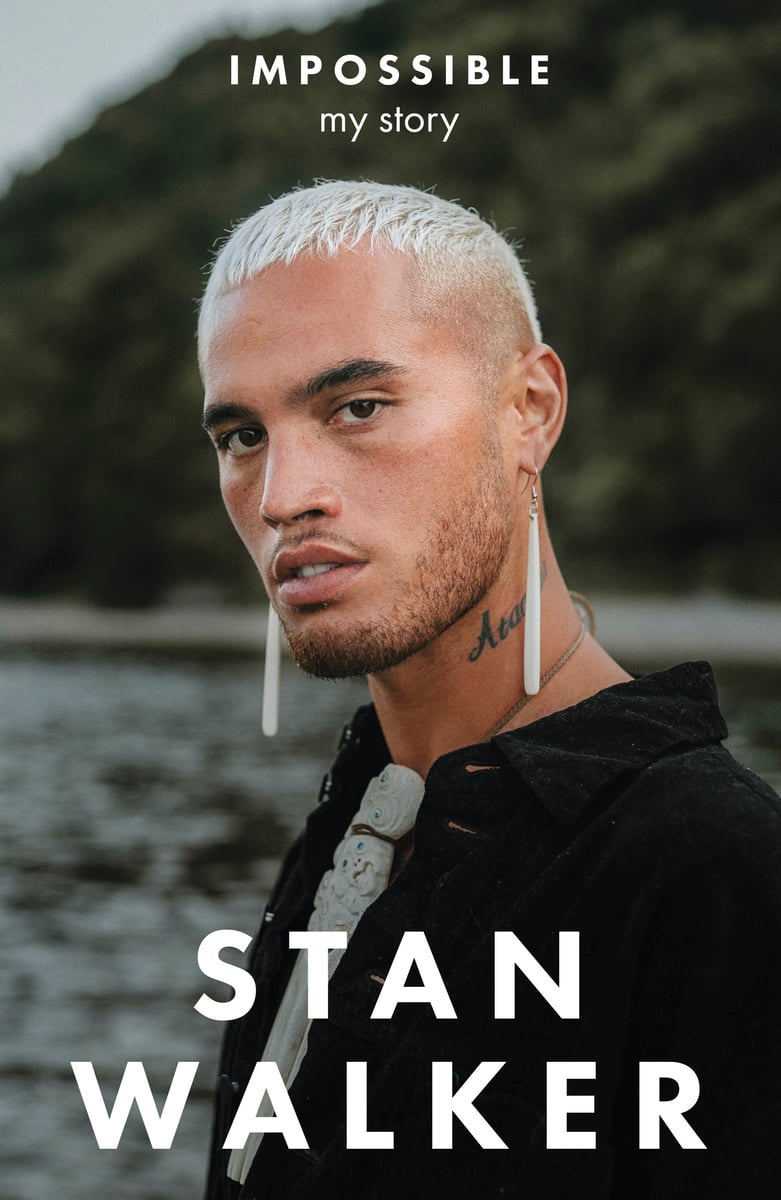

But in this extract from his book, Impossible: My Story, the 'Black Box' singer chronicles a chapter few knew: a childhood studded with abuse, and the backstory that helped him better understand it.

***

I remember looking out my bedroom window. A police car was parked in the drive, sending its red and blue lights flashing over our house. There was shouting. I could see Dad struggling with the officers trying to get him into the car. Then they were gone.

I don’t know who would have called the cops. Mum maybe, if she could’ve, or my Koko [grandfather], who must have often heard the screams and crashes. It’s hard to think of any one specific time, but I just remember watching out the window as Pāpā got taken away. It happened lots of times.

He always came back. Mum always wanted him back. She’d get a bit of strength back and then it would be, "I don’t know what else to do. I’ll go back to him." He would say he’s sorry. He’d say he wouldn’t do it again.

Then boom.

My poor, poor mama. "Don’t go. Don’t go, hun." She’s begging my dad, trying to stop him from leaving. He’s chucking her against the wall. He’s chucking her on the floor. I’m crying. I’m so little. "Māmā, Māmā." Just a little kid, trying to hold on to Mum.