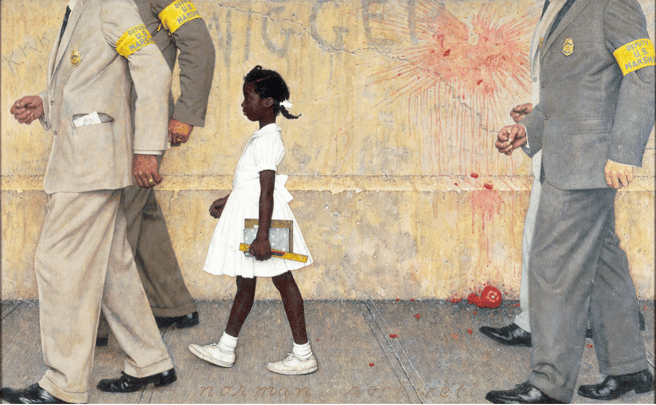

When six-year-old Ruby Bridges walked up and down the steps to her school, she was flanked by white men.

Photos show the small child dressed impeccably on her first day, in a dress and white socks she only learned as an adult were gifted to her family by supporters, as her parents would not have been able to afford them.

She looked stoic as she arrived for a day of education at William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans, and again when she left, surrounded by men hired to keep her safe.

What the photos of Ruby arriving at school don't show is what awaited her: Angry crowds, which she initially thought - with an innocence only a child could have - were celebrating Mardi Gras.

Imbram X. Kendi, author of How To Be An Antiracist, explains why saying "I'm not racist" isn't enough. Post continues below video.

In reality, they were there to protest the racial integration of schools and the idea that children such as her would be learning at the same institutions as white students.

Top Comments