Content warning: This story deals with issues around mental health and suicide and may be triggering for some readers.

On the 9th of April this year, Tony Jenkins, a father-of-two from Newcastle and paramedic of 28 years, was taken into a meeting with two NSW Ambulance managers.

In that meeting, his family now claim, Jenkins was asked about his use of the opioid fentanyl. The 54-year-old allegedly confessed that the trauma of his job had become all-consuming, and he had been self-medicating with drugs he’d taken from work.

The family claim he was then dropped at his car – and, after being explicit about his battle with his mental health and his need for help – was allowed to drive home.

“They didn’t take minutes in that meeting, they didn’t give him a support person,” his 27-year-old daughter Kim tells Mamamia.

“They let him drive home, after he admitted to taking drugs, and after admitting to having mental health problems.”

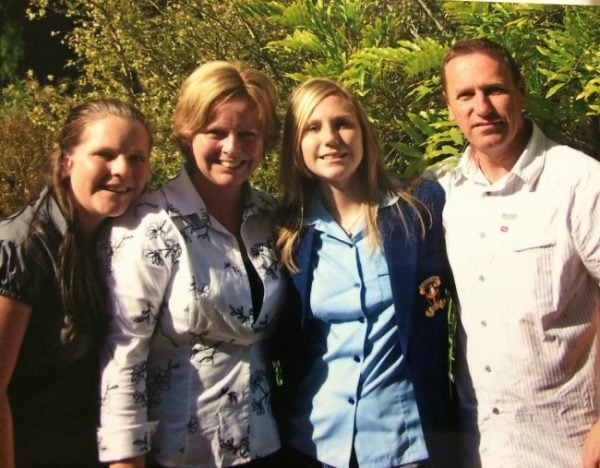

Only Tony Jenkins didn’t drive himself home. Instead, he took himself to Booragul near Lake Macquarie and suicided. He left behind his wife Sharon, 52, and two daughters Kim, 27 and Cidney, 24.

According to NSW Ambulance guidelines, it’s mandatory for official minutes to be recorded in such meetings. NSW Ambulance would not comment on the meeting specifically but told Mamamia they will continue to support the Jenkins family and their workforce.

Top Comments

I worked with Tony on a number of occasions and found him to be one of the best Paramedics I have ever worked with. He was selfless, clinically astute, empathetic, very calm and had a great sense of humour. He was just such a nice guy, will be sadly missed and the world is in a worse place without him.

Some years ago I sort help from the Ambulance Management as I was really struggling at work but at the time did not know what was wrong with me. This help was denied, in fact I was scoffed at by the Manager when I was pouring my heart out. A short time later I attempted suicide but luckily failed. As a result I was hospitalised, diagnosed with PTSD and was medically retired from the Ambulance Service. They then passed me over to insurers where I felt as if I had been discarded like an empty coke can.

Unfortunately there are so many of these terrible stories told by ex Paramedics. Amongst the complexity of each story there is always one factor in common, incompetent management.

My condolences to the Jenkins family.

I am terribly sorry for this families loss and grateful I am not in their position. My husband is being medically retired from the Queensland Police with PTSD and I just needed to put this out there..... There is NO support for members of the QPS. NONE! There is NO policy after critical incidents that they be debriefed counselled etc. In fact what actually happens the member has to put their hand up and say they arent coping. The response, if they want help, they have to sign a form saying QPS can get access to their medical records before they will allow them to access the help free of charge. If it comes out they have PTSD, the QPS have the right to medically retire them. There is no payout or pension - they are just kicked out. Doesnt really encourage them to seek help does it? THAT is why suicide rates are so high. THAT is why they feel trapped and no way out. They take away their identity, they force them into financial crisis and they increase the pressure on the family unit. It is a disgusting way to treat men and women that put themselves out into the battle field time and time again - just to throw them away when they ask for help. How can we change the system?

It certainly needs to be changed, we put so much pressure, stress & problems on these wonderful serving people & there is no help for them in return, it's disgusting & unbelievable!

All the best to your husband & your family xx