As humans, we’ve always had a fascination with the gory thrill of crime and murder.

Even more so if it’s real.

From public gatherings to watch hangings to the police pages of the newspapers in the Victorian era, we’ve lapped up every single detail – the more horrifying, the better.

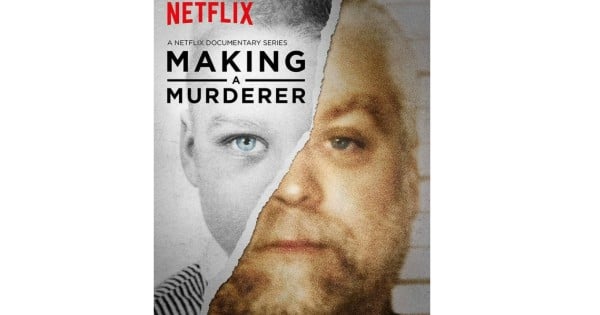

It’s never been so accessible as it is now, with podcasts, books, documentaries and Netflix specials dedicated to retelling the ‘stories’ both older and recent for entertainment’s sake.

So why are we so hooked?

True crime writer Emily Webb on Australia’s most chilling murders. Post continues after audio.

According to New York associate professor of psychiatry Gail Saltz, this fascination partly stems from a small but subconscious inclination to hurt others and ourselves and be “a little sadomasochistic”.

“People want to go see car races not just because they love the racing of cars, but because a car might hit the wall and blow up. There is a fascination with seeing disasters, horrific things,” she told The Atlantic.

Fortunately most of us don’t put these “urges to do something terrible” into practise.

And the best kind of true crime to devour? The mysterious cases that remain unsolved, allowing us to put on our own detective hats and solve them from the comfort of our couch.

Some of the true crime series that have hooked us recently.

"It’s a form of escapism. There’s an inherent need to get close to the edge of the abyss and look in without falling in.," Scott Bonn, a professor of criminology and sociology at Drew University told The Atlantic.

Top Comments

As a producer of true crime series I always include the victims voice. In fact, I find that all too frequently the victim is made a footnote in his or her own story. An example of how this is remedied would be the series Betrayed which is narrated exclusively from the point of view of the victim.

This hit home for me recently, when I was flicking through the Facebook comments under an article about Iceland's low murder rates and a recent murder. One young woman piped up with something along the lines of "so glad I don't live there, I couldn't live without my true crime shows!".

I felt instantly sick. For that woman, murder is purely entertainment.

I don't hate true crime. It's interesting to see what makes people into monsters. It's good to be aware that horrible people exist. And like it or not, it's part of our culture and our history.

But that doesn't mean television networks can't have some respect. Either obtain permission from the victims (or their families), or stick to historical cases where everyone closely connected has since died..

And please please please don't go trying to solve unsolved mysteries where you try to pin the blame on someone very much alive.