WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that the following article contains names and descriptions of people who have died.

For tens of thousands of years, the Aṉangu people lived on the warm, red earth of their country.

The land provided them with food, water and shelter as they travelled around an area we now know as outback Far North South Australia.

But after colonisation, they were moved off their land: forcibly removed, sent into missions across the region and displaced by train lines linking Australia's east and west that impacted their water supply.

Listen: The Quicky investigates the toll of nuclear testing in remote South Australia. Post continues below audio.

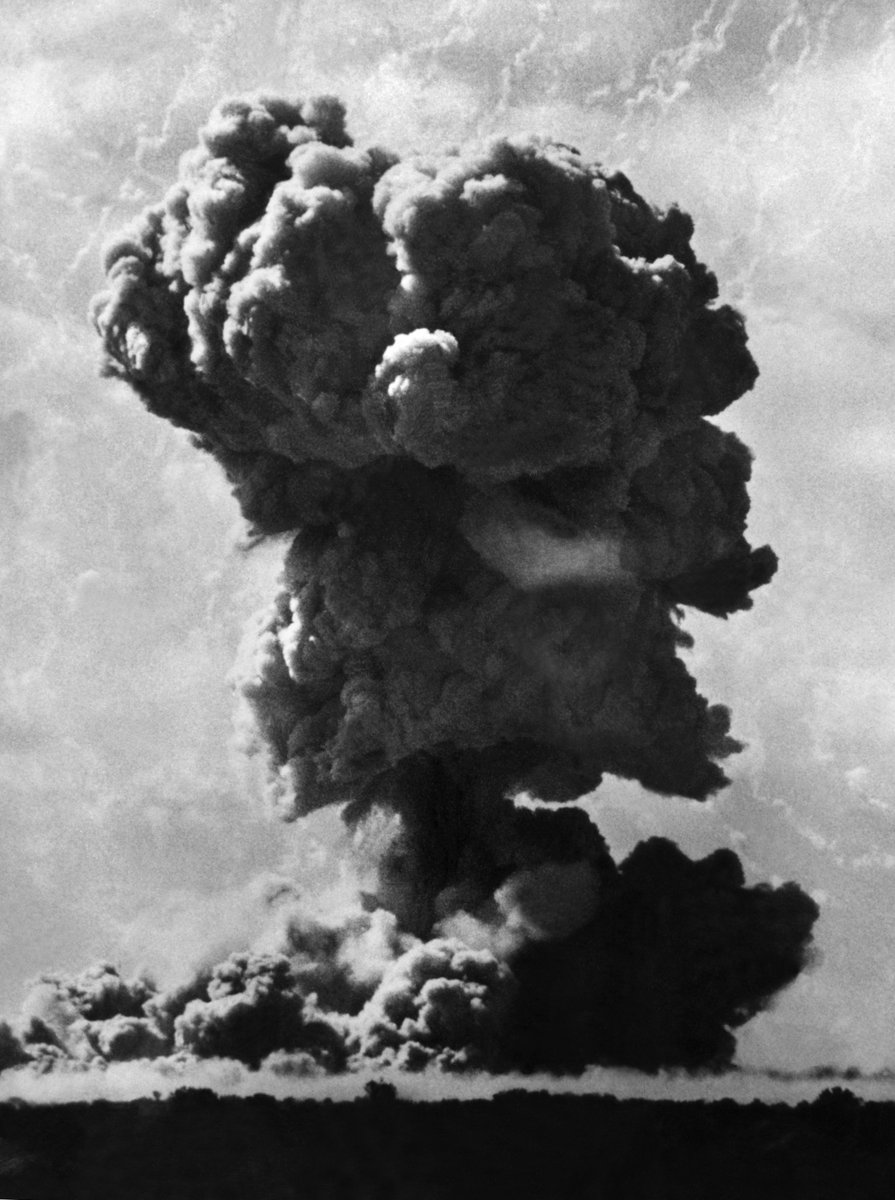

In 1984, the South Australian government handed much of the land back to its traditional owners. But by this point, parts of it were uninhabitable because of British nuclear testing.

In August 1945, the United States dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, bringing a swift end to World War II and beginning the nuclear arms race of the US, Soviets and their allies.

To the British, the vast (and in their minds, uninhabited) lands around Maralinga in South Australia seemed like an ideal spot for nuclear testing, and the Australia Government agreed to "help the Motherland".

Top Comments