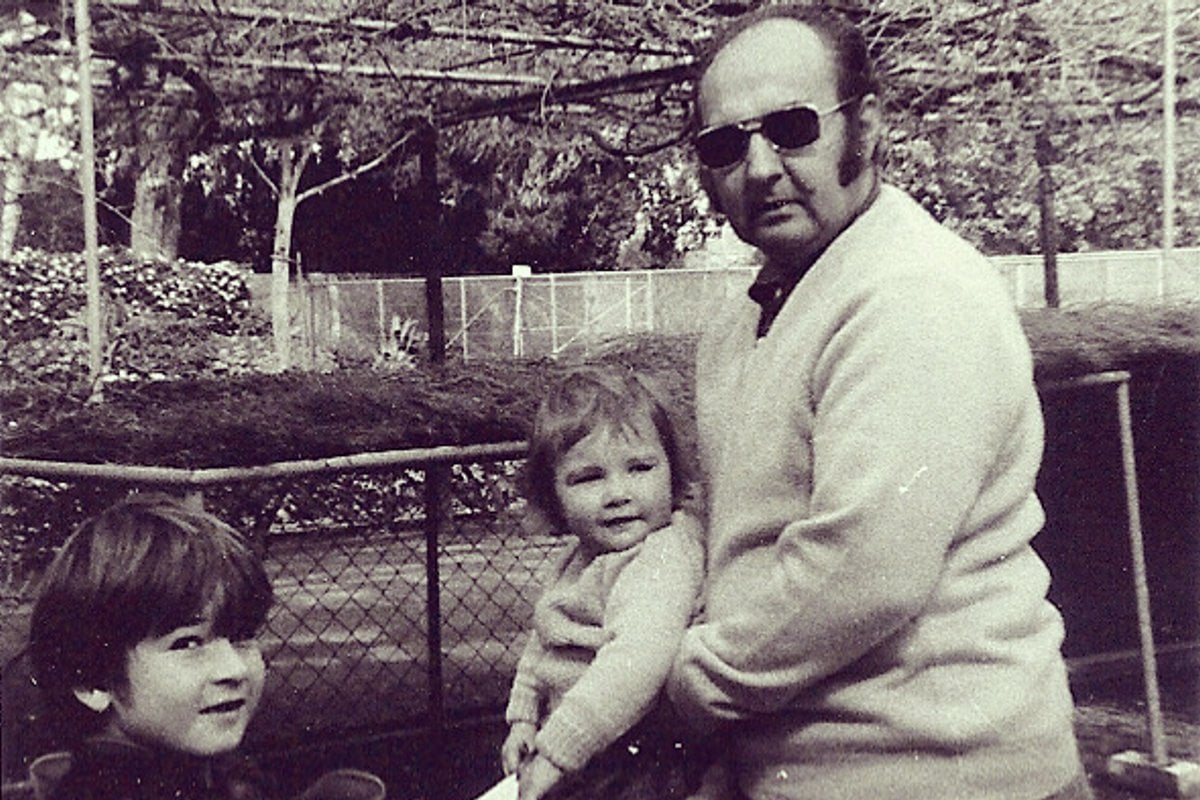

Growing up, my father wasn’t one for conversations. He’d sit on the sidelines, putting up with things until he didn’t, but back then his anger was a puff of smoke with a joke for an exclamation mark. If you smiled, he won.

Today, there’s no joking in his voice. He’s on the phone, announcing that he and Mum are getting a divorce. It’s heartbreaking but not because it’s true. It’s the same phone call that has started my morning every day this week.

“We’ll have to split the assets, sell the house. I need to find somewhere to live,” he says.

“But Dad,” I say, gently. “You have somewhere to live. You’re in the nursing home, remember?”

As he falls silent, I picture him taking in his surroundings – the cold vinyl floor, the hospital bed, the sterile atmosphere that asserts itself through the mountain of photos we put on the walls.

When he was diagnosed with vascular dementia, I dreaded watching him lose his memories to the point of no longer knowing us. But the reality is, there’s no graceful descent – it’s an erratic illness that eats away at the sweetest parts, constantly shifting from one day to the next. And this has been a bad week.

When journalist and author Amal Awad’s father was diagnosed with kidney failure, she made a surprising decision that changed their lives. In this episode of No Filter, she joins Mia Freedman to talk about how we come to truly know our parents in adulthood. Post continues below.

"No one comes," he says. "I’m all alone."

Top Comments