By Minna Muhlen for Earshot.

As a kid, I knew my grandad had fought in World War II. There were reminders of him around the house: the old wristwatch, the strange old, scratchy, grey wool blanket that he supposedly sent back from the war.

But it wasn’t until Anzac Day at primary school that I realised he hadn’t fought on the same side of the war as other Australian grandads.

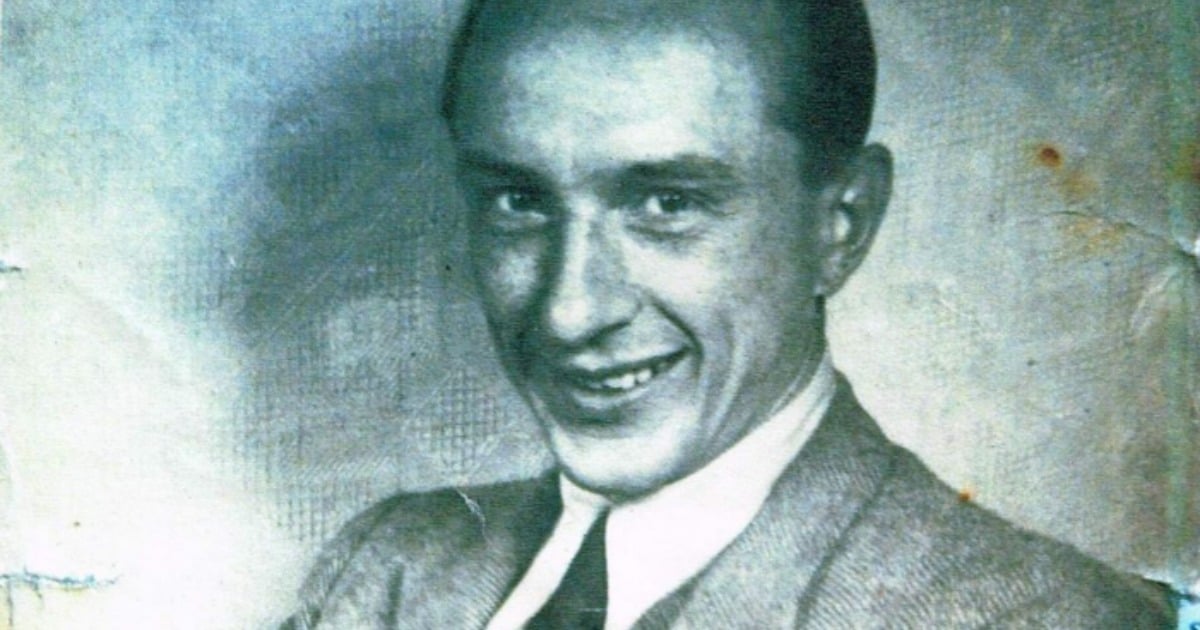

He was Joachim — to us, Achim — a German who died fighting for Hitler’s Wehrmacht, the German army, on the Eastern Front in January 1945.

Over 50 years later, my two brothers and Dad retraced Achim’s last footsteps on a train that wound its way through south-west Poland. Outside it was -30 degrees, one of Europe’s coldest winters since January 1945.

Inside the train carriage Dad was asleep, slumped against the window pane, but my brothers were awake laughing and drinking.

Reaching inside his bag for snacks, my brother accidentally pulled out Achim’s last letter and staring out at a landscape obliterated by ice and snow read:

12.1.45

Dicke Luft! Ivan greift an. [The air is thick! Russians attacking.]

Worked through the night, luggage is packed. Heavy artillery fire. Morale is good.

All my love, always your own Achim.

This letter, scrawled on a piece of lined paper, hole-punched in the left margin, is held in the State Library of Victoria’s manuscripts collection.

It is the last news of my grandfather, who disappeared somewhere between the Polish towns of Kielce and Glogow, three months before World War II ended in Europe.

When I asked my family about this trip they all told me a different version of events, because I think it meant something different to each of them, and because memories always change according to the feelings we attach to them, the story we want to tell ourselves and others at the time.