Content warning: This post deals with stalking and violence and could be triggering for some readers.

Stalker, noun. A person who follows and watches another person over a long period of time in a way that is annoying or frightening.

Ellis Gunn calls him The Man.

The Man in the park. The Man at the auction house. The Man at the cafe.

The Man sitting in his car outside her home.

The Man at her young son's school.

She knows his real name, of course. So too do the police.

But this story isn't about the Man. It's about Ellis Gunn, a Scottish-born poet who lives in Adelaide with her husband and children.

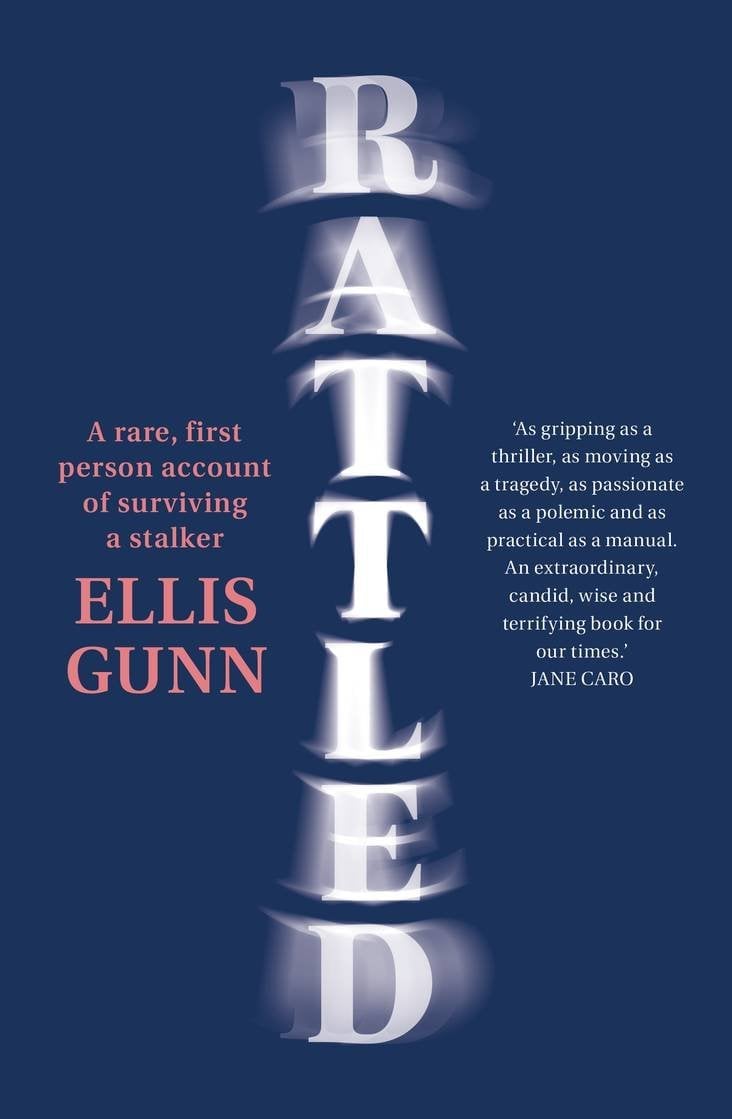

Today, her memoir Rattled is being released, and alongside the usual nerves a writer feels when they let loose a body of work into the wild, there is another emotion Gunn is feeling: fear.

Listen to The Quicky's episode on coercive control. Post continues below.

"It's quite nerve-wracking. My concerns around potentially the stalker finding out... I mean, he hasn't been around for years. And I don't imagine he's interested in me anymore," Gunn tells Mamamia. Her voice is warm and quiet over the phone; her Scottish lilt pleasant.

"But it's just the idea that he might google my name out of the blue and realise that I've written about the experience. And then if he reads the book, he's definitely going to be angry about that, I would say. Because he's a stranger, I have no idea what he's capable of.

Top Comments