By Imogen Brennan.

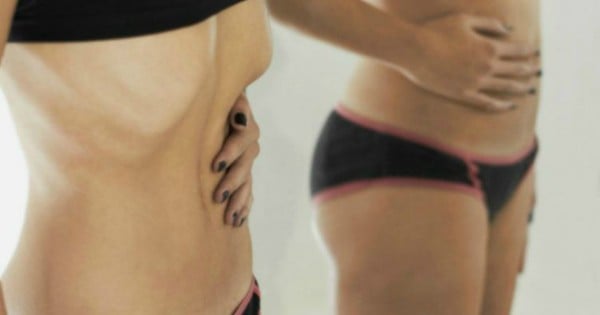

Trigger warning: This story contains a portrayal of a young woman’s struggle with anorexia nervosa and may be triggering for some readers.

The Beginning

I remember the night clearly. It was after school on a hot Wednesday. I was in grade 10 in Brisbane, 15 years old. I’d changed out of my school uniform into a short denim skirt and singlet, and caught the bus into the city for my modelling class.

For as long as I can remember, I wanted to be a model. I was a tall, skinny kid who loved playing netball, travelling, watching news religiously, and fashion shows, too.

That night, my new model agent handed me a book and said, “Take this, the weight will fall off in no time.”

Little did I know that book would change my life.

It was a calorie counting book. I remember thumbing through the pages and having no idea what it all meant. I put it aside for a couple of months.