Michel was still lying in the hospital bed when it became clear she could not care for the baby she had just given birth to.

The hospital knew. Her family knew. Michel, herself, knew. And all anyone wanted was what was best for this eight and a half pound baby named Simon.

It was not a surprise that 28-year-old Michel couldn’t care for a baby. The family had spent her pregnancy researching options and asking uncomfortable questions.

If Michel put this baby up for adoption, the little boy or girl would be fostered for two years until it could be determined whether or not they had a disability. Then, the state would try to find a suitable family for a child who might have greater needs than others their age.

This was because Michel had an intellectual disability. So did her husband, Ron, who was the baby’s father.

In that hospital room, a decision was made by Philip and Beryl, Michel's parents, both in their 60s.

Listen to this week's episode of No Filter, about Michel and Simon. Post continues after audio.

They didn’t want their grandchild going into the foster system. If this child did have additional needs, they would rise to meet them. There was a way they wanted this child raised, and they believed they were the best people to do it.

We know what happened in the days, weeks and years following, because the people standing in that hospital room were our family.

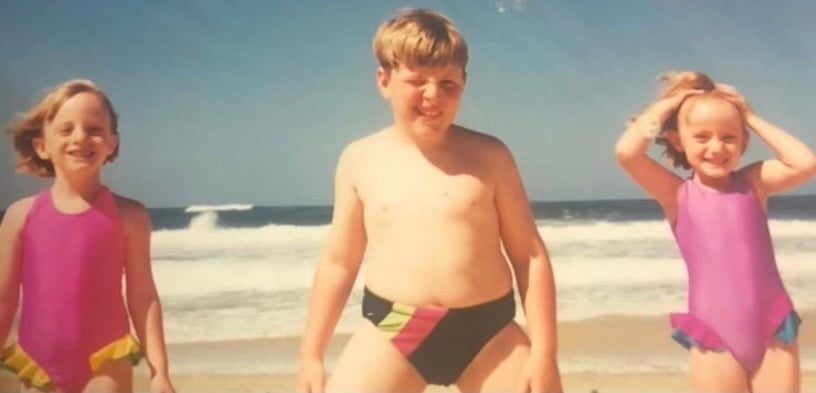

Michel is our aunty, Simon our cousin, and Philip and Beryl our grandparents.

Top Comments