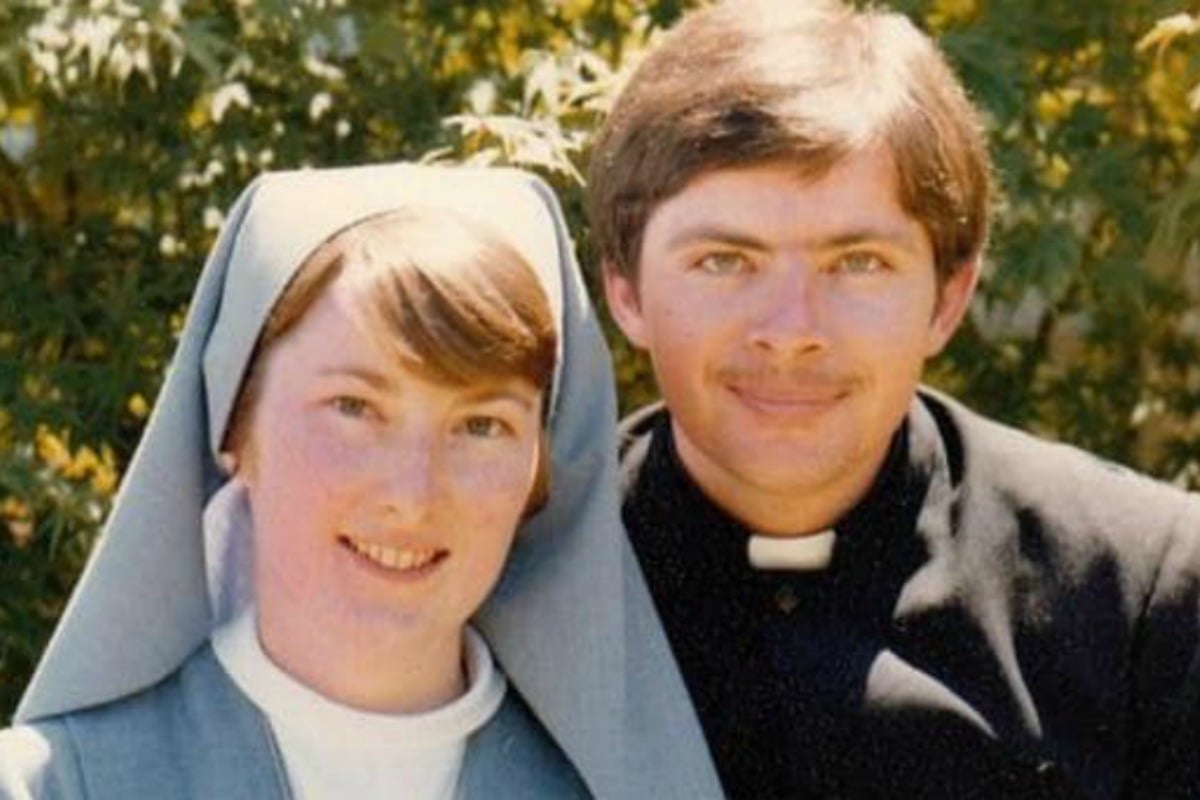

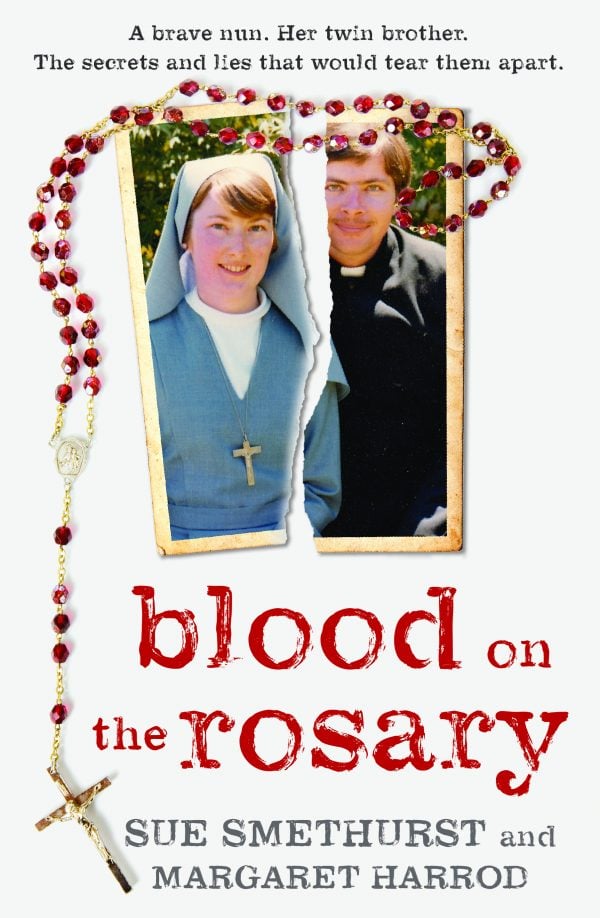

Father Michael Aulsebrook was once the pride and joy of his family.

‘My parents considered him almost saintly,’ Margaret says. ‘The day he became a priest was the happiest day of their lives.’

In March 1987, at the age of 31, Michael was ordained at the local Catholic church. As Margaret recalls, no expense was spared for the occasion.

‘It was a huge celebration. You couldn’t wipe the smile off my parents’ faces. It was such an honour to have a priest in the family.’

Margaret’s brother had begun his clerical life years beforehand, teaching at Rupertswood College in Sunbury, on the outskirts of Melbourne. Brother Michael was popular among students, often buying the young boys treats from the school canteen and spending lunchtimes with them. One victim recalled how his mother was so charmed by the young priest that on his first day of school, she insisted that if he ever had a problem, it was Brother Michael he should see.

Michael quickly rose through the church ranks and was promoted to the role of school deputy principal, but by then alarm bells should have been ringing.

‘Every school holiday Michael would visit family interstate, often accompanied by a young student, a different boy each time,’ Margaret recalls. ‘They’d stay in hotels and I was really disturbed by this. My gut instinct was that it wasn’t right, but he’d tell us he was giving the boys a break from family troubles and I convinced myself that was okay. I couldn’t contemplate that he’d be doing anything wrong.’

Top Comments

"She battled the Church bureaucracy for years, but heard nothing further until a friend phoned to tell her Michael had gone to jail. "

So let me see if I have this straight: her brother was accused of abusing children, he confessed the same, so her solution was to go to the church (who, unsurprisingly, did nothing), and so she spent subsequent "years" battling church "bureaucracy" ("bureaucracy" being a term for "criminal cover up"). Why didn't she and her sibling go to the police as soon as her brother confessed? Thank goodness someone obviously did, given he ended up in jail - no thanks to the inaction of their inaction after hearing his confession.

They did go to the police. As she said, she found out he had already been investigated prior before she even knew. The police knew. As the daughter of a man who was abused by a priest at an orphanage as a boy, I understand the system quite well. The police can only act on information given to them by victims and informants. Even then, the church stalls, and stalls, and stalls. They were trying to track down the Marist Brother who did it to my father, the church said they had no idea where he was. Dad was talking to someone in the clergy and they told him he was in South America, and they thought the police knew (despite the church lying to them and the DPP), so dad got onto the DPP - Peter Fox I think it was, and they tracked him down in South America and arrested him. If it weren't for dad having a conversation with one of the brothers, the abuser may never have faced court. As it was, he pulled a 'Skase' every time with ill health and an oxygen mask, and eventually the court let him off - after 30+ men testified against him, as he was 'too old'.

I only say this to say that accusing the sister and others of 'inaction' is cruel and abhorrent, way out of line and you really don't understand what the system is like, you are speaking out of ignorance on this.