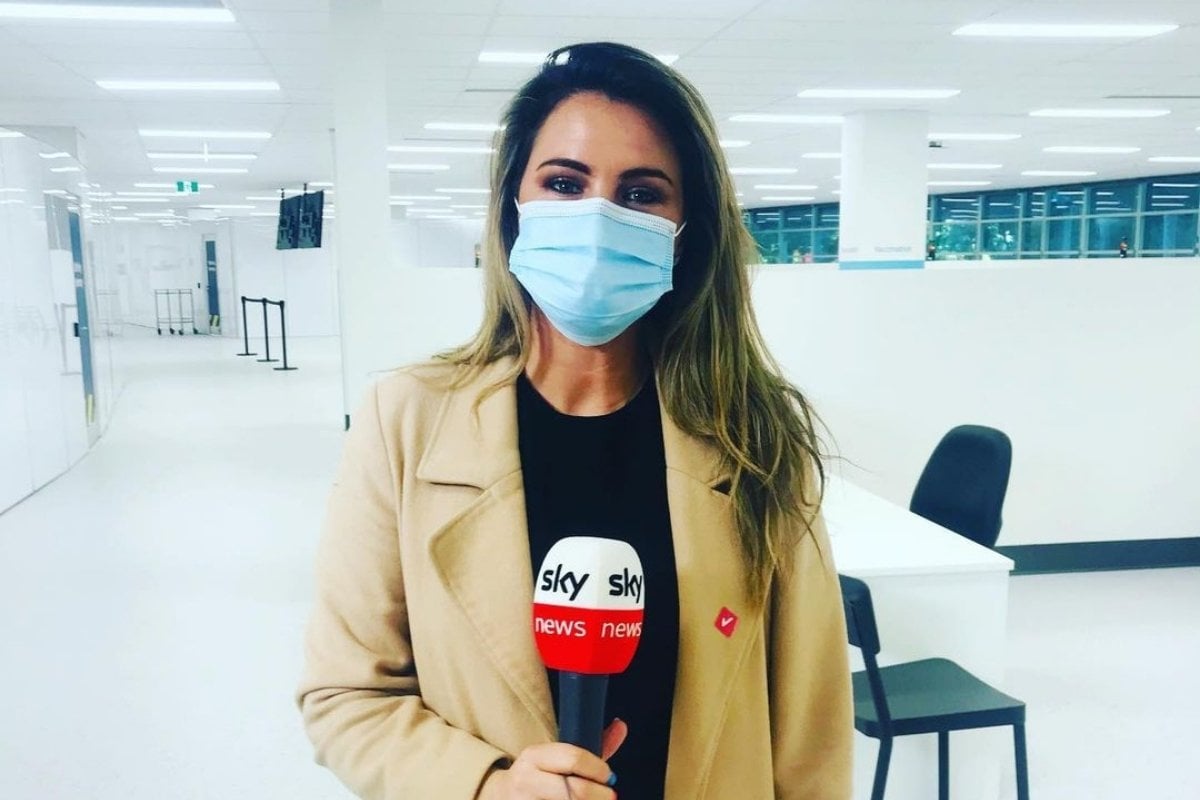

As a television news reporter, Charlotte Mortlock has spent the last 18 months at the coalface of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Sky News journalist travelled directly into outbreak areas chasing stories, attended scores of press conferences, and completed somewhere between 1300 and 1900 live crosses imparting news about the virus.

Then, earlier this month, she announced she had resigned. From the job and the industry she'd loved for more than a decade.

In an Instagram post explaining her decision, Mortlock expressed the toll of being among those who don't have the luxury of being able to switch off from the relentless news cycle.

She wrote about spending more days in the same room as the NSW Premier than her own mother, of knowing that each new cluster meant weeks — potentially months — without a break. She wrote about being attacked daily on social media by viewers accusing her of being too hard or too soft on authorities, and of the sheer weight of her duty as a journalist during a once-in-a-generation crisis.

"The media's role throughout the pandemic has been odd and complex as the Fourth Estate," she wrote. "It's our job to hold the Government to account. And that has never been more important when our lives are so much at their mercy. But it's also our responsibility to echo their messaging because it so drastically impacts the lives of our audience. That responsibility on its own actually weighs quite heavy."

The cost of delivering the news.

While healthcare workers, ambulance officers, police and quarantine officials well and truly held the frontline of this pandemic, reporters are among the thousands of other professionals whose roles have become more critical than ever over the last 18 months.

Top Comments