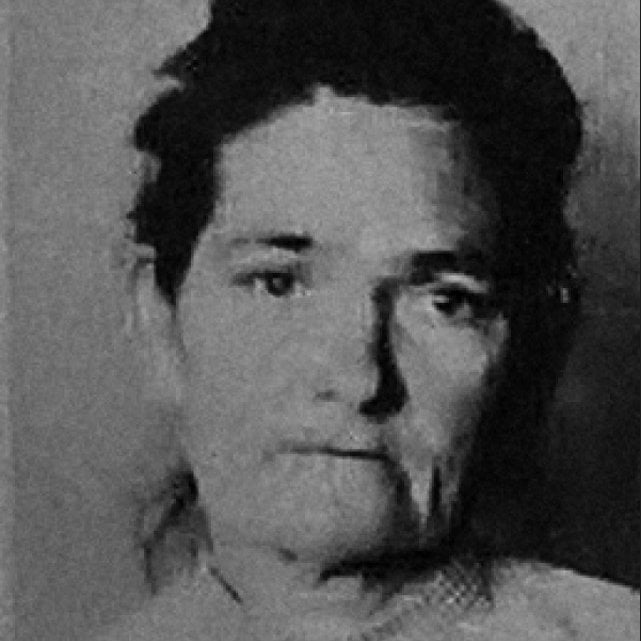

Alice Mitchell has been described as Australia's worst serial killer, and yet you've likely never heard of her. In 1907, the Perth woman was arrested for the murder of five-month-old Ethel Booth.

In the subsequent trial, which gripped the nation at the time, it was uncovered that at least 37 babies had died in Alice's care. In fact, Alice had been running a 'baby farm' – the practice of accepting custody of an infant purely to make an income, and not necessarily to care for them.

The below extract from 'The Edward Street Baby Farm' by Perth author Stella Budrikis, delves deep into the history of how Alice Mitchell's baby-killing crimes were uncovered.

***

Alice Mitchell had no experience in any sort of nursing, other than as a mother of her own children. But no experience was required. Under the state’s Health Act of 1898, anyone taking custody of children for payment simply had to prove that they were "of good character" and register their premises for the purpose.

Alice submitted a letter of recommendation to the Perth City Council from Dr Coventry, a well-respected local medical practitioner. The house was inspected by a health inspector from the council to ensure that it was clean, safe and had adequate room for the number of children being cared for. Once Alice was registered and her premises were licensed, she could legally advertise her services and take on the full-time care of infants and young children.

Most of the babies that Alice received belonged to single mothers, who were unable to keep their infants with them because of the need to return to work to support themselves. A few had mothers who were married but separated for some reason. One father placed his baby with the Mitchells after his wife died and he had no family in Western Australia to look after it.