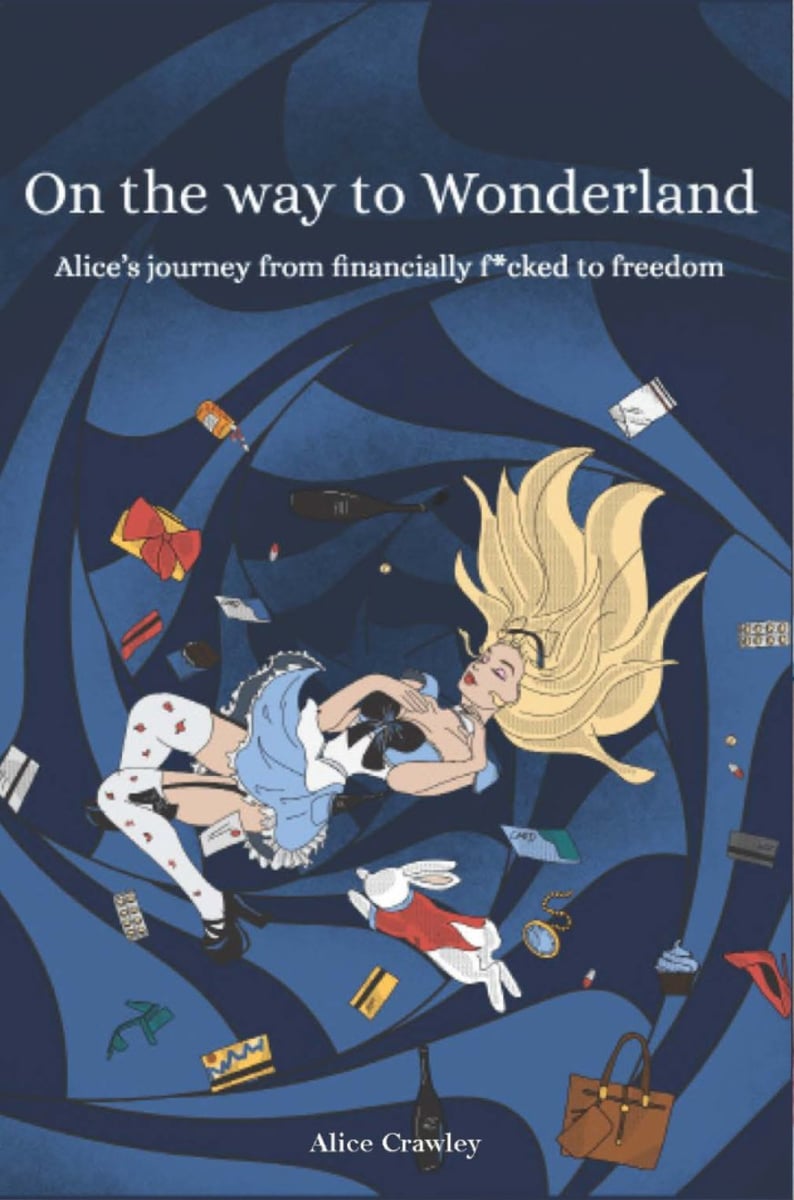

The following is an excerpt from On the Way to Wonderland by Alice Crawley, a book about her journey from financially f*cked to freedom.

It was 1996 and I had returned to Canada right after my epic overdose in Japan. My mother greeted me at Toronto Pearson airport in the back of a limousine, swigging back a 26-ounce bottle of Gordon’s London Dry Gin. My hypervigilant antennae were always on high alert around my mother, and I quickly noted that the bottle was already half empty and it was only 4pm. I was in mild shock while also bordering on wanting to crack up with laughter at the absurdity of the situation.

The first words out of her mouth stung like a poisonous dart: “It would have been a lot cheaper if we just shipped you back in a body bag.” Not exactly the warm and welcoming embrace I’d hoped for after a near fatal overdose in a foreign country. Good fodder for my next therapy session, I thought, or another story for my book – I had been banking those from around the age of seven. I was no stranger to her sadistic sense of humour – she might as well have said, “Off with her head!”

Let’s face it, I was well committed to getting off my head. I’m sitting there thinking, FFS, this is serious, Mother. But this was the only way she knew how to communicate what I knew to be one of her greatest fears – through her drunken and sardonic humour. Mom had a golden rule, which she reminded us of at least weekly; none of her children were allowed to die before her because she couldn’t live with the guilt. This always felt a bit heavy over Sunday spaghetti night, but she was never one for light conversation.

I always sensed that buried below decades of delusion, she knew our family was deeply dysfunctional. She would have had some acceptance, surely, that I didn’t overdose in Japan because I was sick of eating fish and rice every day. It may have contributed, but only slightly. She got it. Nothing needed to be said. Nothing could be said.