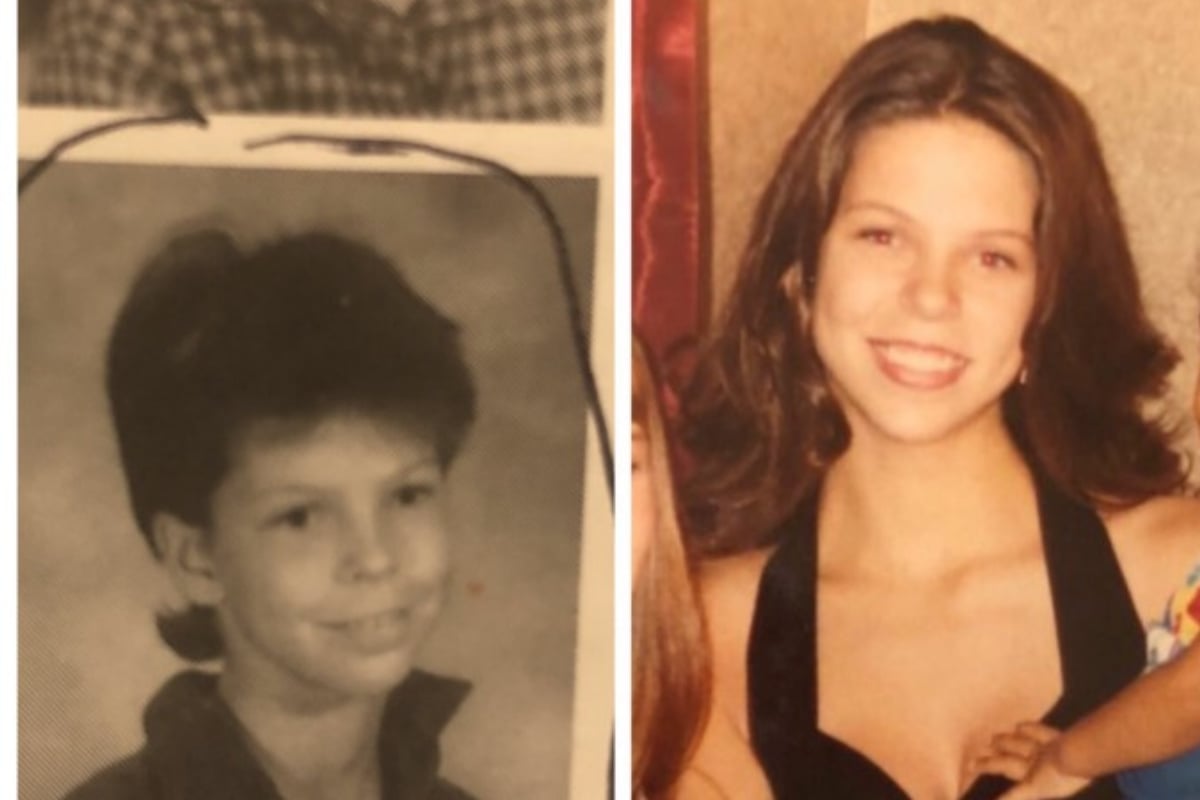

From ages six to about 12, I was perpetually lonely. I would ride my bike around the neighbourhood in the same circle around the same blocks over and over again. I read constantly. The kind of reading where you zone out and don’t hear people calling your name and they have to shake you to pull you out of it.

I had collections of things. Bells and dice and ribbons and Barbie shoes. I would line them up and stare at them and rearrange them in patterns that were pleasing and satisfying. I didn’t brush my hair. It didn’t occur to me. I mean, I tried to make it look okay but I could never really get it to look like everyone else’s and it really didn’t feel that important anyway. At least not yet.

To say that I struggled to make friends is inaccurate, because the truth is that I didn’t have any at all. I didn’t understand how relationships like that worked. I would try to be nice and smile and tell them about whatever current book I was reading, but they never seemed interested. They would giggle and whisper and make jokes that I didn’t understand. I ended up just chasing them around the playground because when I tried to talk too, they would laugh and snicker and run anyway.

Side note – Kathy Lette on why we should change the way we view autism. Post continues after video.

Top Comments

Whether you chose to send your daughter to a mainstream or specialised school, she’ll turn out to be a secure, well-rounded, happy individual - because she has a mum like you. There are many paths to a successful and fulfilling life and I’m sure your daughter will find hers.

And don’t worry, there’s not one of us out there who doesn’t find communicating with our ex unpleasant!!