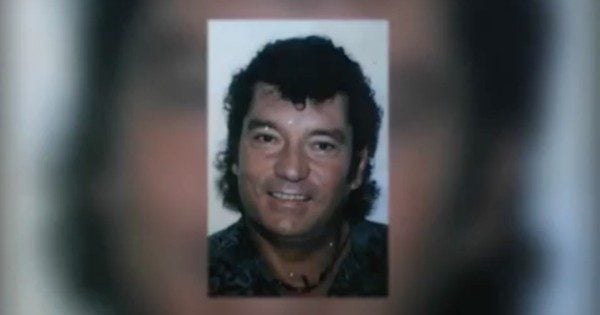

When Katherine Knight murdered, skinned and cooked her boyfriend, John Price, she cemented herself as one of Australia’s most notorious killers.

The murder, which took place in March 2000, was so horrific, Knight was the first woman in Australia’s history to see the words “never to be released” on her court papers.

Women don’t kill often. It’s what made Knight’s crime that little bit more shocking.

According to data held by the Australian Institute of Criminology, women make up just 14 per cent of killers in this country.

LISTEN: To the story of Katherine Knight. Post continues after podcast.

Rebecca Butterfield is another notorious Australian female killer.

While serving time in Sydney’s Silverwater Prison after stabbing her neighbour, drug charges and malicious damage, she fatally stabbed her cell-mate 33 times.

Now in her 40s, Butterfield is still in prison on an extended detention order despite already serving her time for manslaughter.

Then there’s Keli Lane. She’s also in prison for murder.

Convicted of killing her newborn baby in 1996, hers is a controversial case as she is still considered by many to be innocent.

Three women – three very different stories – but according to criminal psychologist Tim Watson-Munro: “They’re all bad, not mad.”

Top Comments

There is a show called deadly women that looks at cases like these and is absolutely fascinating.